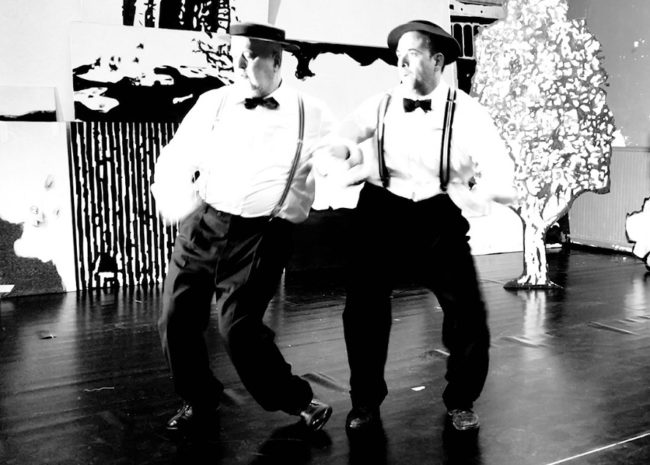

In the beginning of August or at the end of Impulstanz Festival, depending on how your summer is measured, Yosi Wanunu, the artistic director of toxic dreams and conceptional artist Roland Rauschmeier (WTKB, Wiener Tanz- und Kunstbewegung, with Anne Juren), join forces for a dynamic performance. skug met the Buster Keaton impersonating pair after a rehearsal of »The Deadpan Dynamites – The Art of the Gag« in the cellar of the Austro-Marxistic building Thuryhof, the Viennese home of toxic dreams for over twenty years. Even without their porkpie hats, creamy cakes, and spritzing flowers, the meeting was enlightening, entertaining, and delightful…

skug: Let’s start with last words. Buster Keaton’s last words on his deathbed were supposedly: »Why can’t I give up at last?« Was he trying to say something to you, the Deadpan Dynamites? Why can’t you give up on t/his kind of humour?

Yosi Wanunu: I have been personally working on and off with silent movie and elements of the humour of Buster Keaton for quite a long time. Generally, using the idea of comedy as a genre or style to tell stories is very much part of how I see the world. I love Buster Keaton because I think that for a long time he was dismissed as just a funny guy. It took a long time until the 1970s for people to discover that this funny man is actually a great artist. He is a good example of well-done comedy in the heights of comedy. In my opinion, his work is the pinnacle of slapstick.

Roland Rauschmeier: Hard for me to say what he meant with it. During the rehearsal process it was very funny because Yosi mentioned T. S. Eliot saying: »Sometimes you have to kill your darlings.« In this project we don’t kill darlings, we give birth to a mammoth. So I cannot relate to this remark. But generally, I am very good at not finishing things.

The tradition of Vaudeville physical comedy was largely handed over to the gloved hands of comic figures in the 1920s. How do you see your chances of reversing this development, why did you pick up the physical aspect of it?

YW: The original Vaudeville performances had many different elements. It was a kind of a variety show with actors, musicians, acrobats, magicians… The physical comedy was the most famous part of Vaudeville. You could also have someone playing a very classical music piece as a virtuoso who could play it in a funny way. Actors recited poetry or delivered a big Shakespearian thing. If you have a look at the film »The Playhouse« by Buster Keaton, you get a good idea of how Vaudeville could look like. It was a mix of many, many things that American TV later adopted in the 1950s.

The reason I am interested in Vaudeville is also: something happened in the beginning of the 20th century. Theatre was taken over by plays as art form of the bourgeoisie. Hendrik Ibsen and Anton Tschechow were taking over the stages, William Shakespeare became very big. And theatre is basically leaving the theatricality, the fun behind and becomes much more a serious place for people who think they are more cultured. Vaudeville and variety shows were the areas of the working class. Humour with culture, or what I always call serious fun.

I was very attracted to it because politically it was the most radical and sexiest place in terms of how the human body was presented and what was allowed or not allowed.

People nowadays are interested in Burlesque, which was part of the Vaudeville tradition. And for me it was very interesting because it kept the form of theatre that is not based on the playwright but on the moment and the body and the theatricality of physicality. That’s why I always come back to it because I don’t like theatre based on plays. Of course, I love text, but this is a different issue. And musicals, but that is a different issue, too.

RR: I studied conceptual art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, and I am considering myself a conceptual artist. So I enjoy playing with different genres, forms, formats and contents. Yosi is so enthusiastic about Vaudeville, so I get in contact with it. It is a very interesting physical experience to do it as seriously or aware as possible, but of course we have physical limits.

YW: I am sure that in a Buster Keaton film we would have been side characters, the fat guys who beat everybody. Me at least…

RR: You have to say something about virtuosity. As a part of the research process we watched a lot of movies of course and it is amazing how well-trained Buster Keaton was and how he used his body. He was really a trained sportsman. So we are far away from copying him.

YW: No attempt to copy him or Charlie Chaplin…

As mentioned before with the gloved comic figures. What and who would be the continuation of Buster Keaton nowadays?

YW: Buster Keaton influenced a lot of different people – both in comedy and not in comedy. For example, if you look at someone like Jackie Chan: he is a big fan and copies in his movies almost everything that Buster Keaton did. From tricks with bicycles and falling off a wall to whatever… But on the other hand, if you look at Johnny Knoxville from Jackass, he is also a big Buster Keaton fan.

Peter Bogdanovic made the movie »The Great Buster: A Celebration«, where he interviewed a lot of actors and film makers like Quentin Tarantino or Mel Brooks. They talk about the influence Buster Keaton had on filmmaking because he was the first who started to tell stories physically via camera. Everybody could learn from him because when you look at silent movies before him it looked very much like filmed theatre. He was the first one who started to understand where to position the cameras and how to tell a moving story.

I don’t think he was intellectual in that way, it was an innovative and intuitive way of working and trying to figure things out. Buster Keaton was a good mechanic, he could really build things. He once said, if he were not an actor, he would be an engineer. There is a scene in »The Playhouse« where he films himself about ten times. When you look at it you ask yourself: How could he do this in the 1920s? Basically, he invented a lens that is cut in pieces like a cake. They film him, then they crack the film back and turn the lens back and film through another piece of the lens cake. The film is exposed again and again for just one part. At the end you get nine Buster Keatons. When you think about it, this technique is very modern.

RR: We spoke about it today during lunch. It could be the amateur movies you find online on platforms like LiveLeak or FailArmy. Personally, I enjoy watching people being completely drunk and lose control. I am also into pimple popper movies in which people squeezing their blackheads and cysts. It satisfies a certain voyeuristic gaze from the public. In some ways, Keaton did the same. Maybe it ended up there.

YW: You are totally right. Actually, think of all those funny cat movies. People can share their sort of silent short movies easily nowadays.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MDgWiMPY6KU

Could you give a little hint of a gag or a joke that you are developing at the moment? Is there something that you could share beforehand?

RR: I think the relationship between Yosi and me is already ridiculous. Because he is a Jew and I am a German. Whenever he says something I say: »Oh, sorry!«, or: »Excuse me.« But in any case, he is the victim.

YW: For example, we take this idea of »cake in the face« and we try to see what we can do with this joke and we end up hitting ourselves instead of the other person. We turn the gag into self-affliction. And then it goes on to a scene where the cake in the face becomes very erotic, almost kinky. It looks more sexual than a gag, actually. This is how we extend it. Or we take a simple scene of the wedding ring gag. In many silent movies there is this gag with the rings. The ring is missing or not fitting…

RR: Don’t tell the whole show!

YW: No, no. I am just explaining the gag, not the show. We do take on this moment, a proposal. And, of course, first of all you have two men doing it. Then we play with variations. While working on it we decide at a certain point that it should be raining. So we need umbrellas and me really loving musicals, I realise the similarity to »Singin’ in the Rain«, so I start to work on this scene.

The couple thing is a staple of »Laurel and Hardy« or the »Odd Couple« or whatever, or later when you look at movies like »Rush Hour« or this good cop, bad cop police comedy idea. But what is interesting with Roland and me is that we are physically not the opposite of each other in that sense.

RR: Yosi and I are similar enough to be quick on a professional level. But at the same time, we are different enough to surprise ourselves during the rehearsal work. That’s a pleasure. We don’t re-do Buster Keaton. We had to find our own angle. Usually we start from an image, and then we set it into motion.

YW: How do you execute a gag with props and bodies, what are the mechanisms? How can you turn a normal action into a funny action? Of course with our physical limitations. A stupid example of a gag: you can cut a cake with a chainsaw. If it is funny or arty, that’s a different issue… But that is how you start to think about it. It gets interesting for us when our own bodies and conditions produce comments.

So it is more of a deconstructive act or approach?

YW: Yeah.

RR: No. I would say it is a progressive act. We start from somewhere and then we see where it gets us. We are not analysing it to get a deeper truth. Deconstruction for me is a term from a post-modern discourse.

YW: We deconstruct in the sense that the audience sees how the joke is being build. This is what we do in a couple of scenes.

The term slapstick comes from commedia dell’arte. Clowns used sticks to imitate the sounds when they hit each other. What you think about violent elements in humour?

RR: I had a big discussion with my 12-year-old son, who sent me a video recently. It is one of those videos that I mentioned before. But there is one scene were someone gets severely hurt. I tried to explain to him why this is not funny anymore and that watching it is nothing I can support. Vaudeville, as Yosi mentioned before, took place in a contained environment such as theatre. If you pretend that something mechanically brutal is happening, nobody really gets hurt.

YW: Trying to avoid violence is kind of an illusion. In order to push the body or to get to the point where things are funny, you have to push yourself. Buster Keaton is a very good example of it because he started to act at a very young age and his father was basically banging him into the wall. That was very funny back then, but the British Social Services and the police didn’t think so. They wanted to take Buster Keaton away from his father. They had to get away in a boat back to America.

And when you look a Buster Keaton’s movies: he doesn’t have stunt people. Why did »Jackass« and brutal internet memes became very funny? It is juvenile, it is almost part of growing up in a certain way. Of course, not everybody should do it! When Roland and I are trying out things, there is a level of aggressiveness that is necessary in order to execute the gag. A cake in the face is an aggressive act. Even if you just spritz water with a flower in the face of another person, it is aggressive behaviour. But for me slapstick is built on these routines and it can be a release for people to watch it.

You have the same discussion with porn. Is it actually reducing violence or not? I don’t know. I think it needs a certain amount of aggression. In theatre you can create drama and conflicts via words. Already the Greeks knew it back then: first you need a tragedy and then there is the release where you can have a drink. In Vaudeville the conflict is a physical conflict and in order to have a physical conflict you have to have a certain friction.

Of course, there will be people who can do it very politically correctly without violence and I would be interested to see. I am very curious because nowadays we are changing our way of dealing with life. But back then kids were beaten. My father used to slap me (he was a Moroccan man) and that was the way he educated me. When I see spanking nowadays, I still relate to it in a painful way. My son – I treat him like he is made of sugar, of course – when I show him Buster Keaton, he still laughs a lot.

Following the idea of violence. How vulnerable do you feel when you are the person who is having the gag made upon? What is the impact, is one of you the more vulnerable one on stage?

RR: It is an easy technique: you have a master and servant situation. The person who is used to being passive is very much supporting the other person who seems to be violent, because the more quiet and passive one is, the stronger the action of the other person can get. There is a passive-aggressiveness forcing another person to get into motion, get into action. It is an interesting interplay. The seemingly lesser aggressive person might be the more aggressive one.

That sounds like life…

YW: There is a vulnerability in exposing ourselves. But me being 50-something, I feel quite at peace with who I am and my body. Maybe people who are watching us think that we are brave in that sense that we expose ourselves, but I enjoy it. You use whatever you have.

So vulnerability is disappearing in the work after a while. It gets very normal to do things with Roland when it becomes a daily routine. At the moment when you start to use your body as material you lose the fear. This is one thing that comedy can teach you: you really need to have trust!

RR: Yeah, it is a burden to carry him…

Do you see the concept of performing deadpan (pan was a slang word for face in the 1920s) more serious or do you see it only as a vehicle of comedy?

RR: In my personal experience, it is not so complicated to be serious. Being funny is very difficult! And for me the highest level is to be funny and very sad at once. And that is incorporated by Buster Keaton. Today, when we rehearsed the last scene, I felt very funny and very sad at the same time. Let’s see if we can land some jokes on that level.

YW: In a way deadpan is a very modern idea. Because in the performance scene, there is this idea of non-acting and just being yourself. I don’t think it was the intention back then. But Buster Keaton understood that when everyone around him plays different commedia dell’arte characters he can become the centre when he is not overproducing emotions, artistically. By distinguishing from the others, he becomes »everymen« and that, I think, is very smart. After the Second World War, with Samuel Beckett and the absurd theatre, and the time when big acting was over, it became very clear that deadpan is a very modern concept of a performance technique. Samuel Beckett did a film with Buster Keaton and you could see how Beckett takes his comedy and turns it into something totally existential. He understood that it might look funny, but it was really existential.

RR: This is the main performance technique now. People just carry out a concept, performers usually are not allowed to have facial expressions because they are just there to execute someone else’s concept. They are not representing a thinking human being. Personally, I am a little bit bored by this status quo.

I would like to add that that is the case with a lot of classically trained musicians, too. They are not allowed to make too much eye-contact with the audience.

YW: But let’s get back to the 1920s, even if it is hard from the perspective of today. Think about it: people didn’t have television and hardly photography. The close-up of a human face in the size of a film screen could shock people.

What about theory, I would just like to mention the quite influential book »Le Rire. Essai sur la Signification du Comique« (»Laughter. An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic«) by Henri Berson from 1900. Does it mean something to you?

YW: It is a very dear book to me because it is one of the books that describe quite well how laughter and comedy work. And it is a personal topic for me because when I moved to Europe 25 years ago, I had this feeling that people here look at comedy as a second-rate thing. For me it was difficult in the beginning because I came from the tradition of New York and the people I worked with like Richard Foreman or the Wooster Group. They employed physical comedy, it was their main thing. All of these questions: how laughter works, what comedy does to you.

People tend to think that drama and tragedy are closer to life and comedy is artificial but actually, when you think about it deeply, comedy is much closer to our lives. Our lives are much more built form the smaller moments when we make little mistakes. Not the higher ideals from drama and tragedy – it is just how we want to see ourselves. Comedy is much more about how we actually are. And most often we don’t want to see how we actually are. After many years of being in Vienna, I am now happy that with toxic dreams we managed to convince people that there is a value in this technique. Henri Bergson analysed back then why we laugh and that was a very new thing because the concept of laughter is related to Aristoteles. He considered comedy a lower style.

RR: Not at all, he lifts it onto a higher level than drama. That is one reason why »The Name of the Rose« was written.

YW: That is a speculative thing. I am not so sure if the assumptions of »The Name of the Rose« are historically accurate. We have to read Aristoteles tomorrow as homework. Maybe it will become a part of the show…

RR: Ha ha… very funny.

You mentioned the physicality of what you are doing and your body limitations. How do you train, or do you just work with what you have got?

YW: We cook every day for our kids when we are at home after the rehearsal. And I walk to the rehearsal space. If I need to learn a dance or a movement, I usually watch the video first and copy it. Today I spent half an hour trying to copy Gene Kelly singing and dancing in the rain. Not really successfully yet. I might look like a big falafel dancing with an umbrella. I think I need real rain and a very good umbrella, then of course I can do better.

RR: I have to train my handshakes.

Thank you very much and keep your humour…

RR: Which one?

»The Deadpan Dynamites – The Art of the Gag« is performed on August 5th, 6th, and 7th at Schauspielhaus: https://www.impulstanz.com/en/performances/2019/id1303/