Following an invitation by TONSPUR Kunstverein, Leah Singer and her husband, Sonic Youth co-founder Lee Ranaldo, are currently residing in Vienna’s Museumsquartier as Q21 Artists-in-Residence. During their stay in August 2022, they have created a sound installation accompanied by a septempartite photo series and an indoors film-installation. skug talked with the vivacious couple about their creative process, influencing the mainstream and the democracy of public art.

skug: I was thinking we could do three different things: 1) talk about your current projects here in Vienna, 2) your collaborations, and 3) I’m curious about a few motives that appear in your work.

Lee Ranaldo: Let’s start with what we are doing here this month. We’re creating sounds and visuals for the TONSPUR_passage in the MuseumsQuartier, and a video work for the TONSPUR_display nearby. Two separate but related projects.

Leah Singer: They’re related in that an important aspect of our collaboration here at MQ is that we came with nothing, no ideas, no materials, no resources…

L. R.: No preconceptions.

L. S.: No nothing. Beforehand, we only saw photos of the passage. I think that’s the key. These projects are linked only in being done site specific.

L. R.: We’ve been generating all the material that we’ve been working with while we’ve been here. Absorbing the city as much as we can.

How do you approach a project with the program of not involving preconceptions?

L. S.: Organically. A new place offers a lot of creative opportunities, so you’re building knowledge on the spot.

L. R.: We are also playing off of how we work and work together. It has both, you know?

L. S.: We can’t deny that we come to a project with all this history. That’s just going to seep in through osmosis. But I will say that certain materials and places suggest what the project is. To me, Vienna really presented itself very quickly. Lee as well.

L. R.: Yeah. I’m working on a local instrument, a German-made parlor guitar from the 1930s, I think. It’s just all been falling into place like that. I bought some bells at the flea market, here at Naschmarkt.

L. S.: A little Glockenspiel and another large, heavy bell.

L. R.: I slowed the recordings down a lot, and manipulated them, so they won’t sound like the natural sounds. The thing about the passage is that the sound level must be kept very quiet, so the piece has to work at low volume, as an ambient atmosphere for people passing through.

L. S.: 65 dB.

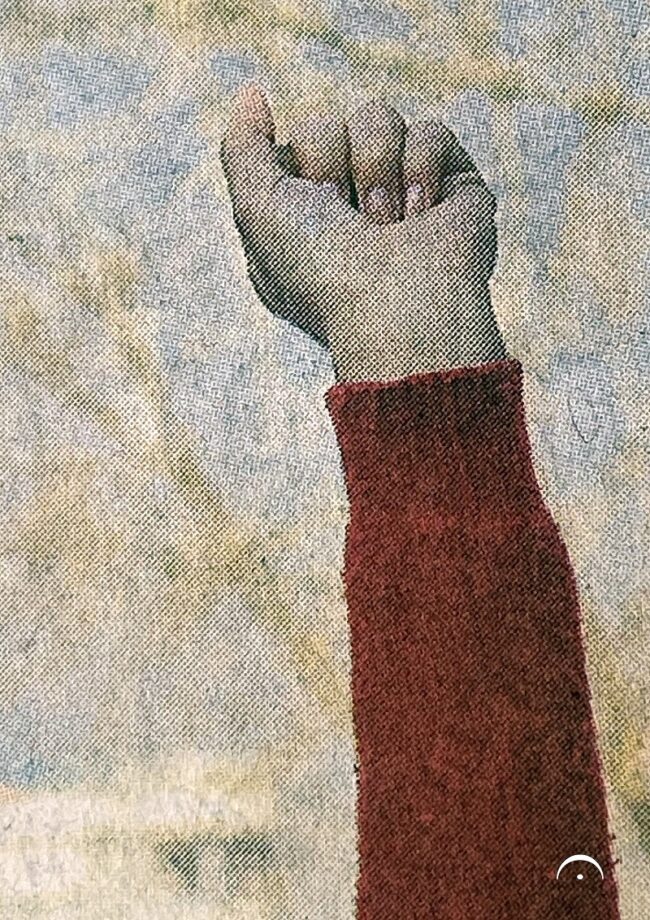

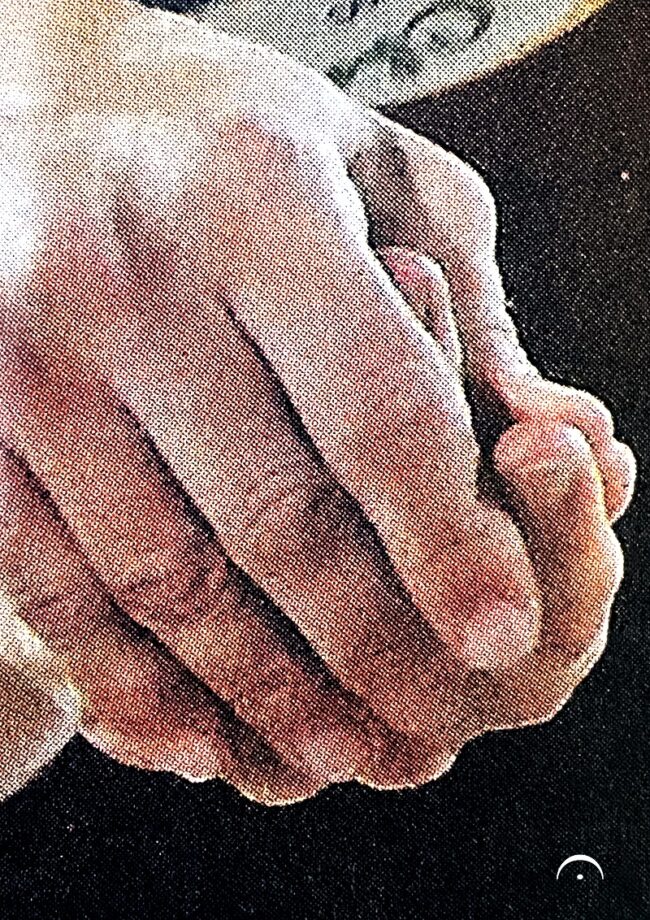

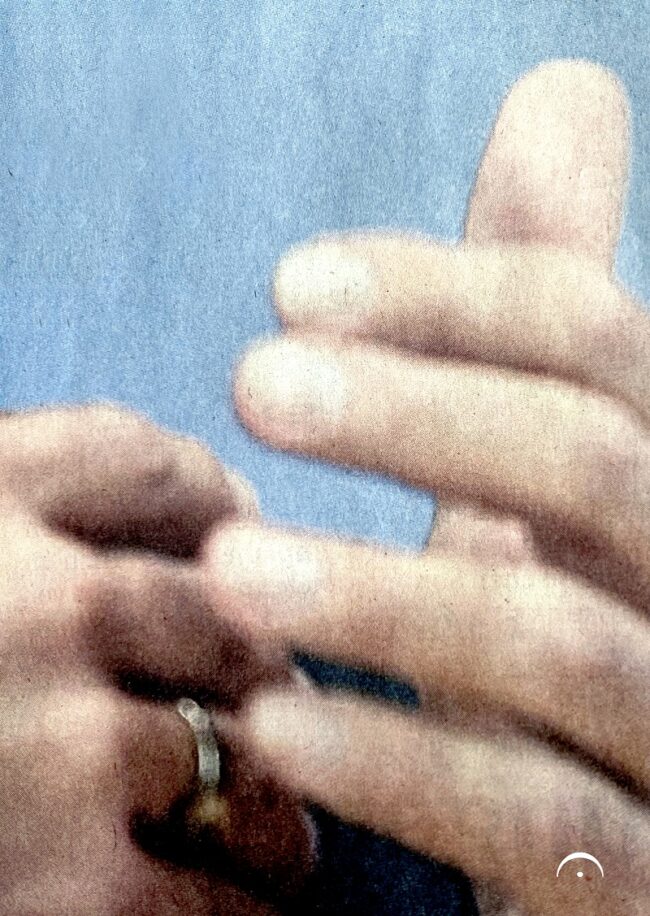

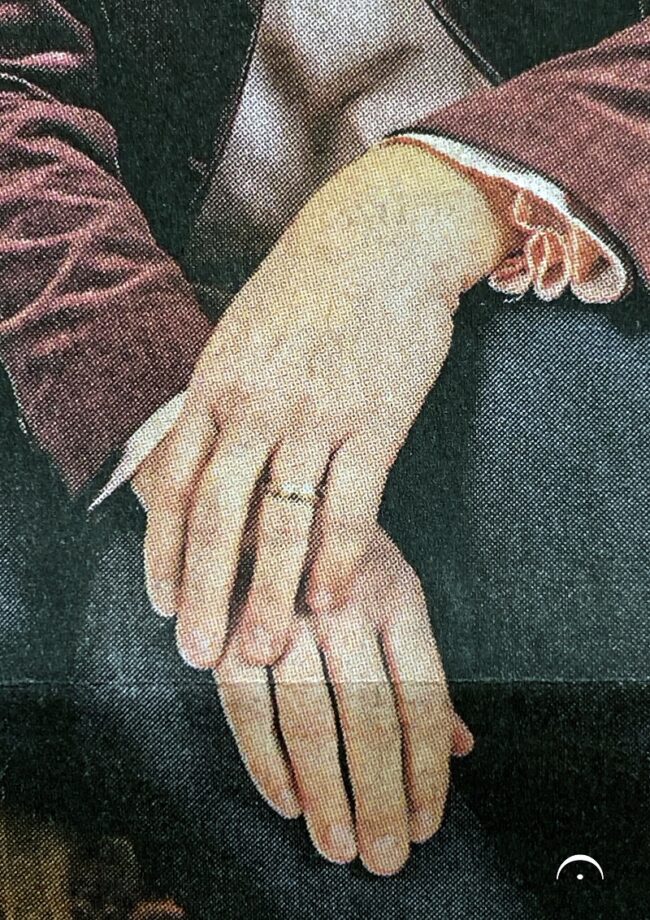

L. R.: The music must be environmental in a certain way. When we were doing tests in the passage, it sounded good. I’m really happy with what I’ve got going.

L. S.: We should talk about the title of that work in that passage. It’s called »Fermata«. »Fermata« is a musical term. On a chart it indicates a moment of freedom for the performer. The performer can improvise in that notated spot. You can cut loose and hold the note, pull the cord, not do anything. It’s freedom, it’s self-expression. We liked the kind of analogy of what that represents. In this moment of a war in Ukraine, of a public health crisis, etcetera, this idea of a pause and freedom resonates. So, we called this piece »Fermata«. Lee works with that from a sonic point of view and I work with that idea from a visual point of view. I’ve created things that I’ve garnered from daily newspapers, mainly Austrian newspapers, where I was re-photographing people’s hands. Seven poster images display hand gestures. Some suggest power, some suggest submission. You can read what you like into these very slight gestures, but it is communication with your hands. As a pause or freeze frame it relates to the idea of »Fermata«.

L. R.: Fermata is the moment in the score where the performer can add a little of their own emphasis. But it also means to pause. We’re hoping that the passage is a place where people will pause and ponder the images.

L. S.: It is a… I’m gonna say it wrong: Gemanstkunstwerk. Germast… Gemast…

Gesamtkunstwerk?

L. R.: Yes, that’s right. (laughs)

L. S.: This has been the ongoing, long-term joke with me that I cannot pronounce it. It’s my favorite word. I love the German language in that you can take one word and have a near universal meaning. And I cannot pronounce it. Gemanst?

Gesamt.

L. S.: Gesamt! (laughs) But anyway, that idea, Gemanstkunstwerk, is what we’re doing.

L. R.: You think so?

L. S.: Yeah. And I gotta say, it is such an amazing term. And it’s something we don’t have.

Usually it’s translated as »total work of art«.

L. S.: I’ve been thinking about this, while going to the Leopold Museum, to the floor of the Wiener Werkstatt and looked at all their work, from painting to furniture, to jewelry, to carpentry. They had the idea that once you indoctrinate people to things that have an aesthetic, they get used to that. If you grow up with an aesthetic, it becomes part of what you know, your education, what you expect in things. I think those artists were kind of brilliant. In that, it makes me think of Gary Panter. Gary Panter is an American artist, comic artist and a fine artist, kind of a hippie and a punk. He contributed a lot to the culture. He’s known for doing all the sets for the television show »Pee-Wee’s Playhouse«.

L. R.: That’s his biggest claim to fame, although he’s an underground comic artist.

L. S.: When he was much younger, he wrote a manifesto, called »Rozz Tox Manifesto«. Basically, it was telling other artists: »Get your work into the mainstream! Because, once it’s in the mainstream, you condition people.« So, it’s like the Wiener Werkstatt. It’s the same idea. And it can be a horrible idea, too. It can err on the side of fascism. Oftentimes, we have this understanding that »well, if it’s art, then it’s safe« or »it’s not dangerous«. But you can easily veer into dangerous territory in the art scene. Art, like everything, is ambiguous. But Gary Panter was saying, you can work with this ambiguity. I agree with that. I think it’s an important way of people learning and accepting other things to break the status quo.

It seems to harken back to the idea of avant-garde as art for a new people?

L. S.: Absolutely! Any movement that introduces something radical and new is breaking the old. It’s trying to break the chain.

L. R.: And there are people that are interested in that. They’re like: »We don’t want to see the same thing again. Let’s see something different. Maybe it will be good, maybe it will be shit, but somewhere in there, there’s someone advancing the vision.«

L. S.: I think you always need to have tension.

L. R.: Yeah!

L. S.: Because everything needs tension. If you don’t have tension, I don’t think you can legitimately see it as heartful. You need tension, in whatever way that represents.

L. R.: You want to talk about »In camera«?

L. S.: I can. The project that’s going to be displayed inside the building is called »In Camera«. In Italian, »in camera« means »in your chamber, in your room, in your space«, but it’s also a legal term. We’re projecting some digital video on this window. Our host Georg Weckwerth and his wife Sabine Groschup took us out of the city to the Heurigen and we shot some video out there and other material around Vienna like at the Belvedere gardens. The video has been manipulated while I’m shooting. There’s no post-production. So, it’s all in-camera. Get it? (laughs)

It’s an interesting idea to have an artwork in the public space that plays with notions of »private« and »public«…

L. S.: Even though we are not focused on that per se, we are sensitive to that. We are cognizant of what that would mean for the person coming through. We even present it that way. »Come through and just walk on. Or stop and pause.« It’s a mirror to the experience of the person who walks through this passage.

L. R.: Another part of being here has been the exchanges we’ve been having with people here. We’ve been reaching out to a wide net of people and exchanging ideas and experiencing the city in a really cool way. All that stuff filters into what we’re thinking about and working on. A month’s not gonna be enough time here. I wish we were here for two months.

L. S.: Very, very, much. There are so many layers to the city. You’ve got all these underground stories. You’ve got all this war history, you’ve got the Jugendstil. It’s fascinating.

L. R.: And, in terms of motives, there’s certain things we’re always working on. It can be the simplest thing. We’re always collecting images and collecting sounds. That’s the basis of all of it. We’re collecting stuff and toying with it.

L. S.: We’re both collectors, whether it’s sounds, or images, or movies, or memories. There’s always this taxonomy of an archive.

A lot of different aspects are involved in your approach of how to combine things.

L. R.: We have a long history between us. And part of the approach has to do with juxtaposition. Just taking two different things and putting them together and seeing what happens.

L. S.: It’s attitude as well. Attitude is a very big thing with anything you’re doing. Ours is pretty open. We have a set of standards for ourselves. But there’s always room to improvise, to be loose about it. »Fermata« is a great symbol of what we do, of how we work as a team.

L. R.: The springboards of our work come out of the electric guitar and the sound of tape manipulation, and avant-garde film. That is a background we both share. Using images in a certain way that’s not narrative storytelling way but poetic. Working with sound in that way, too. It’s not like when a film composer scores a picture. I’m not writing music that scores certain images or vice versa. Whether it’s noisy stuff, whether it’s Sonic Youth, whether is composed or abstract music. There’s juxtaposition. And there our sensibilities are shared.

This relates to something I wanted to ask anyway. If my research is correct, you met each other at the end of the eighties while doing a collaboration…

L. S.: Well, I booked Lee. He worked for me. »I was the boss«, that’s what I like to say. I moved to New York from Montreal via Tokyo in 1988 and got friendly with Michael Dorf, who used to own the original Knitting Factory. I have proposed to the owner of this cool venue that I wanted to do a hand-made instrument festival, because I had seen a German avantgarde guy, Hans Reichel, who had built a crazy musical contraption out of plumbing material. I saw that in New York and was like: »Wow, there gotta be other people that build these kinds of instruments.« So, I planned a five-day event at the Knitting Factory and I solicited people from far and wide from the US. For one of my evenings, I needed electronic hand-made instruments and Michael suggested Lee. We met when he played for the festival. He was really good and interesting. At that time, Lee was using feedback loops and played on a TV monitor. So, he was working with visuals. And that’s what I was doing. I was working with musicians, doing visuals, and trying to find a new balance between the sound and the visual. That’s when we realized we need each other in this performance space. I need sound, he needs visuals. It worked out that way. And we continue it. Ever since then, it’s been variations of this performance. It’s kinda grown, shrunk, expanded as it’s evolved.

It seems to work out so well for the two of you.

L. S.: It has. We have a personal and professional artistic collaboration, and we have a family as well. It’s such a specific and occasionally chaotic lifestyle, but it works for us.

You mentioned earlier that art needs tension. So, I was wondering, how do you deal with tension, conflict and different ideas?

L. R.: Screaming, yelling, breaking of glass! (laughs)

L. S.: Yeah, screaming, thumping on the ground, fists on the tables. It works.

L. R.: Maybe that’s somehow reflected in the end product.

L. S.: But our personal stuff doesn’t get in the way.

L. R.: But maybe the tension of: »I like this but you don’t like it.« That was the whole thing in Sonic Youth. Sonic Youth was four people working on something and anybody that had a weak idea, that idea got thrown out. And you’d recognize that it was for the collective good. That makes works stronger. In the gallery it may end up that we just show stuff that you shot.

L. S.: But you’re in the movie.

L. R.: I’m the star of the movie. (laughs)

L. S.: Actually, our host, Georg Weckwerth is the star. (laughs) In any case, these shots are more poetry than anything. Kind of ethereal. Because that passageway is a walkthrough. You must get people right away. Otherwise, they’ll just walk. We have no expectation that anyone stands there for more than a minute. In that way, it’s almost like looking at a painting. How long does an average person stand in front of a painting? It’s short, generally.

L. R.: The TONSPUR_passage is really cool space to ask sound artists to work in.

L. S.: I’m very excited because I love the idea of public art. I like the democracy of public art. I like that everybody can experience it with the knowledge they have, whether they’re art historians or whether they have no real interest in art, or music. I think you have a responsibility as an artist to do public work.

»Fermata« – Tonspur 91

Lee Ranaldo, Leah Singer

TONSPUR_passage / MQ Wien • 29.08.–10.12.2022 • daily 10–20 h • 9:00 min

»In Camera«

Lee Ranaldo, Leah Singer

TONSPUR_display / showrooms Q21/MQ Wien • 29.08.–26.11.2022 • daily 10–20 h • 6:13 min

Preview in the presence of the artists, Sunday, 28.08.2022, 17 h

Links:

https://www.mqw.at/institutionen/q21/programm/tonspur-91-lee-ranaldo-leah-singer-fermata