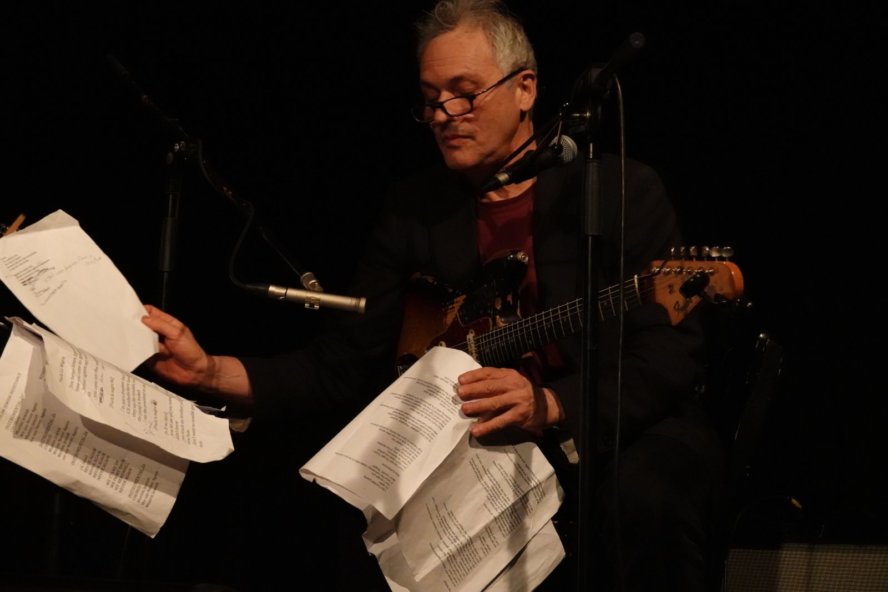

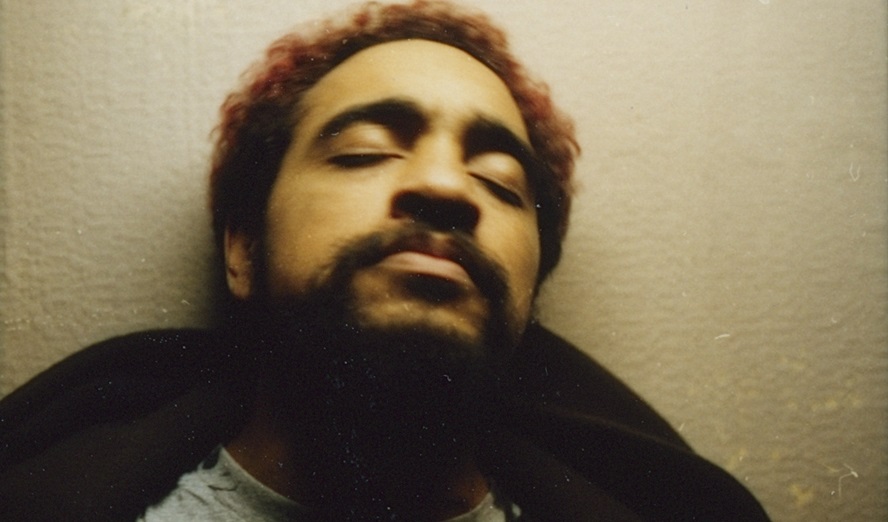

Marc Ribot hat etwas zu sagen: »Fuck you« an all jene da draußen, die mit ihrem faschistoiden Rassismus und Sexismus die Welt verpesten wollen. Der Mann, der mit seiner virtuosen Gangart den Sound mancher Größen der Musikgeschichte mitgeprägt hat, ist wütend – und er hat allen Grund dazu. Seine Band Ceramic Dog veröffentlicht dieser Tage ihr drittes Album – »YRU Still Here«. skug führte mit Ribot, Bassist Shazad Ismaily und Schlagzeuger Ches Smith ein Gespräch in englischer Sprache über die verlorene Politik in der Musik, ein Leben in der Blase und den Zusammenhang zwischen Spotify und Donald Trump.

skug: If we take a look at what is going on in the world these days: How upset should people really be?

Marc Ribot: Well, I don’t think people need to feel upset, but they certainly need to act upset and get rid of these terrible racist and fascist people that are in government right now.

The reason we ask you this question is mainly due to your upcoming album with Ceramic Dog of which you have said that it’s going to be more political than its predecessors. It’s called »YRU Still Here« and leaves us thinking: Who is addressed with this question?

MR: It addresses several people. First of all, it addresses Donald Trump, but it also addresses myself and besides that, it also addresses the audience. A lot of people think that when someone is singing or writing a song, they are singing about themselves, telling the deep truth of their inner experience. Well, I tend to write about the inner experience, but I try to avoid my own. »YRU Still Here« started out as a song about an expression of a teenager to their parents. It didn’t wind up in this way, but in the original version I used to repeat at the end »Why are you still here« until it starts out as a belligerent challenge and winds up as a pathetic whine.

If we take a brief look at your last album with Ceramic Dog, »Your Turn«, how has your approach to make political music changed between these two albums?

MR: Well, we always had some political content in our records. For example, on »Your Turn« we did the song »Bread and Roses« and for those who recognize the tune, we also did »Avanti Popolo« (»Bandiera Rossa«). Although we didn’t do the words there, we had a nice marching band arrangement for this song. I’ve always liked Italian political music, it’s great and can really cheer you up. But let me tell you the story how the latest record happened. So, we were ready to make another record and we already had one about three quarters finished. Then all of a sudden, Trump got elected. Now, I could give a whole speech about how it’s the political responsibility of the artist to respond on this, but what really happened at that moment was, that I just didn’t feel like singing about my romantic disasters. It’s not that I stopped having these romantic disasters, but I felt that we have to get rid of this bastard first and then we have plenty of time to sing about romantic disasters. It was around December 2016, when I started to write a number of political tunes, partly for two very practical reasons. One is that I was playing at some benefits and I wanted some political stuff to play. I mean, I’ve always been interested in political tunes. When I was around 19 years old, I joined the Industrial Workers of The World which is an anarchist labor union. I used to mail in the money and get these little stamps to put in my little red book. We would send each other newsletters and occasionally go and march on a picket line. Anyways, they had a songbook. And that’s why I liked them. You know, I picked the political group with the best songbook (laughs). Apart from that, I’ve been doing songs from American Civil Rights Movement for over 15 years now. Sometimes instrumental versions, but referencing to some songs from the Folkways Records label. I’m also interested in partisan songs from World War II. It’s not that I want to be old-fashioned. When I do these songs, I try not to do them in archival ways but in a reinventing way so that they make sense to me now. There are a lot of ways for music to be political. It doesn’t only mean to talk about politics, you know. One thing that I don’t like about political music is that everybody wants to rage so much against the system. What good is it to rage against the system and then change a chord every four bars? (laughs). What good is it to attack capitalism and then respect the bar line? How can you do one without the other?

Shazad Ismaily: I think that is an extremely important point. One time I was talking to a friend who works at cinema and he was saying: »Why is it that sometimes a person wants to make a radical film, writing very unusual dialog, but when they edit the film it’s a classic three act cinema movie?« This means that the internal structure, the internal form is in dissonance with the external content. So, if we really want to make something radical, the internal form needs to be as radical as the content.

In a way this is like breaking out of the seemingly naturalized discourse and tear it down to make place for something new.

SI: Yeah, the form is something that an audience person takes in nonverbally. They are taking in one message that is saying: »Be conservative.« And then their taking the exterior message that is saying: »Be radical.« When both messages are in dissonance with each other, they are not supporting one another in order to make a heavier statement or a heavier sensation.

MR: Well, as I was saying. We could give a whole rap about how we started writing these tunes because of the political responsibility, but really, we are a rock band. As such, what we mostly wanted to do is rock the house. It’s just that at a certain time after the election of Trump things felt different, the same words felt different and therefore we thought that we needed to sing about certain other things in order to rock the house.

All of this is pretty much linked to another project of yours which is called »Songs of Resistance«.

MR: That’s right. I just started to write some tunes which I was singing at different benefits we were playing. Also, I was wishing that those were songs like at the demonstrations. You know how it is when people chant the same one sentence over and over again. This drives me crazy. Gotta think of something longer, so that everybody can sing something.

Why would you think that people should listen to old songs, when there actually should be new songs?

MR: I agree a hundred percent. Besides, I also don’t think that people should have a politics based on the old songs or on nostalgia. For me, I started going back to the old songs because the newer ones that I was hearing did not represent this very particular moment. I mean, it’s not that there is no political music, but there is not a lot of political music for this particular present. A lot of political music is very specific – like Riot Grrrl or Queercore or, you know, »Elvis was a hero to most, but he never meant shit to me« (Public Enemy, »Fight the Power«). You won’t get white rockers pumping their fist to that even though it’s true – and that Public Enemy CD was definitely my favorite CD at that time. Anyways, what I wanted to go back to was not only political music, but the political music of popular fronts. There hasn’t been much music that can fit that description. I wanted something that a popular front could sing. Not that there even is a popular front right now. I just thought that, maybe, if we wrote these songs, then there would be one. We are working on it, right? (laughs)

Something like a song book for demonstrations!

MR: Well, I am not that ambitious. I just want to make my record.

It would be terribly necessary, though! Some people argue, that today we have the choice between a played-out yet politically engaged music of the past and a meaningless sound of the present. What are your thoughts about not having political music for the 21st century?

MR: You know, Hannah Arendt wrote that the first people to coin the phrase »revolution« were the American revolutionaries describing their rebellion. What they meant by this term was a return. The reason all these buildings in Washington D.C. have columns in front is because they imagine themselves as returning to the Roman Republic. Mind you: not the Empire! There’s a difference which has sadly been forgotten in time. Americans forgot that the Empire was the end of the republic (laughs). So, the Art Ensemble of Chicago always had a phrase »Back to the Future«…

Ches Smith (shouting from the very back of the room): »From Ancient to the Future«. Actually, »Back to the Future« was a great movie from 1985.

MR: Thank you, Ches Smith, for saving my ass again! But anyways, I had the right fucking idea, right? (laughs) Well, in a way it’s the way Jazz musicians work on tunes. You take something historic from the past and you alchemize it into something new. That’s the process that worked for me as someone coming from Jazz. My high school rock band even used to do a mixture of Doo Wop tunes and MC5 covers.

Besides all of that, you have various other projects going on which cannot be pigeonholed very easily. Let’s suppose for now that you’re part of a Jazz scene – whatever that may be. What would you say about this scene considering the political approach?

MR: I think this has always been part of the scene in a way. Just take a look at Archie Shepp with his album »Attica Blues« and… (turns to everyone in the room) Who was that other sax-player from the Sixties? This one guy who used to curse all the time in Spanish? (nobody has a clue) What I am trying to say is that there was no shortage of political jazz. There was in fact a strong connection. When John Coltrane was doing his later stuff, the Black Panthers were in the house and inspired by this.

What about today? For me, I have this picture of jazz musicians in my mind living in a bubble playing for bourgeois people…

MR: That question makes me afraid to ask what the ticket price is. You know, this is a big problem. Part of the reason that one might get that impression… (Ches Smith, the only vegetarian of the three, places a can of sardines on the table) Oh great, sardines! (picks one with his fork and continues) Well, when you create a music situation where you have to make a record in order to tour, you need to pay 20,000 dollars of recording gear, pay a publicist and take months of unpaid time to work on it. And then you say: »How surprising, there is only a bunch of upper-middle class people with the same perspective here, it feels like a bubble!« You know, I came from a middle-class family in New Jersey, but when I came to New York, it was a very mixed scene. That is not so true anymore, but maybe that’s just the scene I’m on. I’m sure, there are people coming from a lot of different perspectives, say in HipHop. Ultimately, in the Jazz and Indie Rock scene, you need so much money to get into the game. That is a form of structural racism.

This brings us to your activism for labor rights of musicians. You’re actively speaking up against YouTube and digital exploitation.

MR: I feel kind of ambivalent about it sometimes, because it’s not like I want things to be more expensive for anyone. In fact, I like the idea of free access to culture. But there are ways to provide that access without screwing the people who make it. As I said before: If you do create these situations where all the risk is on the people who are making the record, you can’t be surprised if you get a certain kind of homogenized culture.

What are the main problems musicians are facing these days besides that?

MR: I name one: YouTube! (laughs) There are whole university departments writing roomful of books about this. The argument with all of them is: You can’t sell what people can readily get for free. Period. As long as that’s the case, we are fucked.

SI: Let’s say it’s totally fine that people can go on YouTube and listen to any record. What upsets me is that while they are doing that and while I’m giving the record away for free, there is a third subject making incredible amounts of money. I think, that is the ultimate difficulty and it feels like the ultimate solution is that if someone is gonna make a million dollars in advertising money, that needs to go to the people making the art that is selling these ads. It’s not that I say: »Hey, audience person! It pisses me off that you can listen to my record for free.« What pisses me off is that while they are doing that, some third subject is making money. There is nothing fair about that.

That’s rentier capitalism, basically. There are a few companies making significant amounts of money without ever redistributing. Do you think there is still a possibility to change for the good?

MR: I think, there are a lot of illusions about this. One is, that there would still be something like YouTube. There are a lot of things of mine on YouTube that I would want to stay on YouTube. The problem is not that things are for free. It’s that things are for free without my consent. It’s not that people are getting things for free, it’s not the free part, it’s the exploitation part that’s difficult. At first, I thought that the horse was out of the barn, but the reason why the current environment exists, is because of a single law – and there is a counterpart here in Europe. In the United States, it’s Section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1997 – which was long before YouTube and Facebook and even before Google was very well established. This Section is one law, one sentence, really. And it says that online corporations will be given a safe harbor protection from liability for third party infringement. Just to be clear: This was a good law in the beginning. At that time, the phone companies were laying the fiber optic lines to enable the internet to grow. They needed to know that they were not going to spend billions of dollars and then getting sued because someone used their pipes to transmit a Rolling Stones song. It was a good thing that the law existed in the beginning. But then very smart lawyers said: »Wow, we can use this law to create a business model – as long as we don’t upload ourselves, we just build a huge field and say woohoo, come on!« If that law was changed – and it doesn’t need to be eliminated because the people who build the pipes should still be protected and there are many fair use exemptions from copyright that should be protected – all these major corporations which have clear knowledge of their site being used for mass infringement would lose their safe harbor. If that happened, this problem would be fixed tomorrow. As you can see, the problem are corporations with hundreds of millions of dollars in capital uploading hundreds of thousands of (music) titles in order to sell advertising brokered by Google. In a way, it’s like drugs. It’s one thing to acknowledge that some people are going to take drugs hiding in the corner and another to sell crack at Walmart. The problem is not the technology. The technology is absolutely wonderful. It’s the law which surrounds the technology. Unless that is fixed, well, don’t be surprised about that feeling of a bubble.

Obviously, those are all good points, but I’d say that most people do not really understand – or worse: they do not even care about the problem that labor rights for musicians are in any way important.

MR: That’s right! This is what I’ve learned during this. People don’t understand most laws. Anything about the digital environment is just too complex. I didn’t believe that I was right until I started talking with David Lowery, the frontman of the band Camper Van Beethoven. In addition to being a musician, David is also a mathematician who teaches music business. Whenever I talked to other people I’d say: »Wow, what is going on with this whole situation (for musicians)« and everybody would say: »No, it’s going to be better than ever.« And I’d argue: »But the record budget just got cut in half« and they’d say: »Don’t worry!« But then I’d tell: »All these people are just using my music for free. You just don’t get it.« So here’s the thing: Lowery is a bit younger than me which means that he went to school with the people who built the internet. And he started saying: »No, actually you do get it, and this is fucked up!« (laughs) Just to make this clear: If this one law passed, we would all still be there tomorrow with tons of stuff, but it would be stuff that’s voluntary. A lot of the political people I talk to advise me not to say what I’m going to say right now: What we are really talking about is that the subscription services will go up by ten dollars. And I don’t wish anybody to have to pay ten dollars more, okay? But you know what? You go out, you order an extra beer and you pay ten dollars at a Yuppie bar. I think that culture should be subsidized in order to be accessible. No kid who wants to listen to something should do without. That’s what libraries are for. That’s what free concerts are for. I’m just very suspicious when there is a politics that says that you can’t pay ten dollars a month extra for streaming. That’s an anarchist politics which defines that as its only political object, well, saying nothing about the price of food or the price of housing. I’m ready to make music for free, when I get free health care, free housing and free food. Let’s go, let’s make it all free. And until then, reality is that there needs to be some kind of market.

You pointed out a lot of important thoughts, really. At last, if we take a glimpse into the future – ten years from now – what would the political situation for musicians be like?

Music has always been difficult, it will never be an easy way. If they reformed safe harbors, I’ll go back to play music. Things will take care of themselves. That’s what we can hope for in a smaller situation for musicians. One other thought: There is another little law that nobody knows about which says that unions can only go on strike against their immediate employers. You have to be defined by the government as a worker, as an employee, and you can only go on strike against your immediate employer – that law is called the Secondary Boycott Provision of the Taft-Hartley Act, but it has its corresponding laws in every country in Europe. I would trade copyright for that, if we could go on strike against streaming companies! A lot of people don’t know this, but a few years ago Taylor Swift withdrew her material from Spotify. That’s legal, that’s fine. But if she had said to me: »Let’s all withdraw our material from Spotify«, they could have put her in jail, take everything she ever made and ever will make. If a union did that on her behalf, they could have arrested the officers, take their pension funds, cease its building and put it in receivership. Give us the right to strike against Spotify, give us the right to strike against companies which ads are brokered by Google, and they could keep all the other laws. This would solve all the other problems too, including Donald Trump.

skug-Artikel über das aktuelle Ceramic-Dog-Album »YRU Still Here«:

https://skug.at/ive-got-the-right-to-scream-like-an-idiot/

Sarkasmus rules: Ceramic Doc ließen sich kräftig für Songs zu »YRU Still Here« inspirieren:

Link: http://marcribot.com/