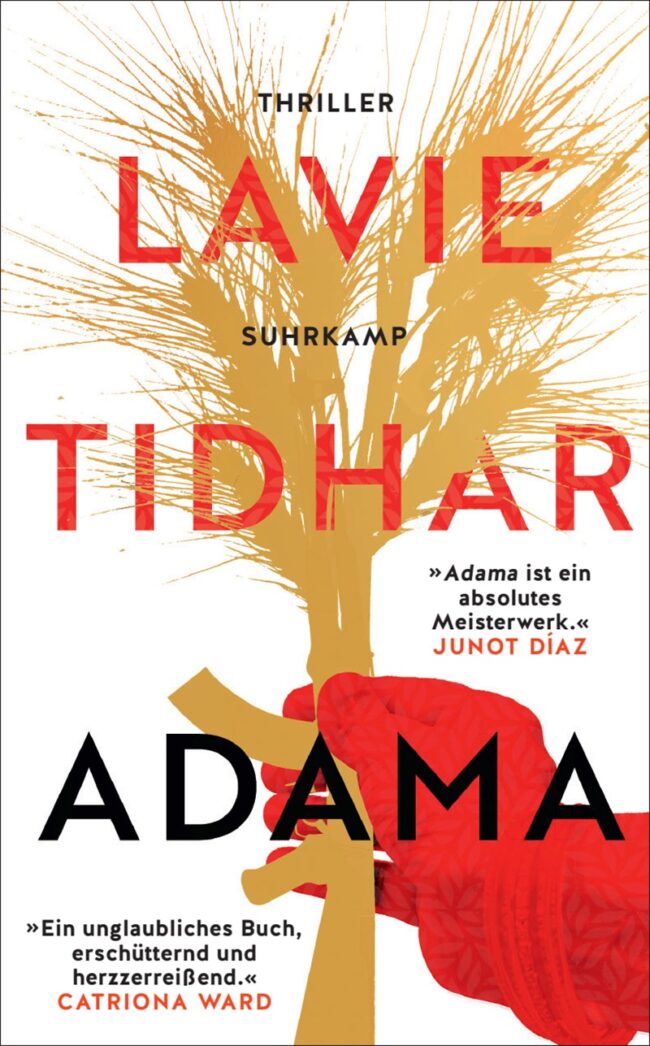

After publishing the first part of the trilogy, »Maror« – one of the best thrillers of 2023 – Lavie Tidhar now releases the second volume, »Adama«, in German, while the third book, »Golgotha«, has just been published in English. »Adama« means, on the one hand, »earth«, but also »ground«. In the context of Tidhar’s novel, the title carries multiple layers: it refers to life on the kibbutz, to the deep-rooted connection with the Israeli land, but also to the weight of history tied to that ground. Like its predecessor, which is set in a later time period, »Adama« makes use of multiple perspectives to tell its story. Three different generations, three distinct viewpoints: people who have lost everything and sacrificed everything; their children, growing up in a new socialist society – the kibbutzim; and their children, already more or less disillusioned, who have drifted away from the early ideals. The narrative moves back and forth between time periods, offering insights into daily life, the psyches of survivors and their descendants, the struggles to preserve dreams, and the battles with inner contradictions – between necessity and resentment, the fight for survival, and personal desire. The story revolves around murder, drug smuggling, old and new ideals, love, and affection, and it begins with a man returning to his former home – only for the past to catch up with him faster than he could have expected. The founding of Israel as a crime story. We spoke with the author about the extent to which he himself is part of the story, and what is invented versus what is taken from reality.

skug: »Adama« is the second book in the »Maror« trilogy. What does this story mean to you personally, and what was it like working on it?

Lavie Tidha: I found working on »Adama« very difficult, because it was a book outside of my comfort zone – it’s a family saga, not a type of story I had really attempted before. Though weirdly, my next book immediately after that, »Six Lives«, was another – if very different – family saga, and for some reason I thought that one would be easy! Which just goes to show I have no real idea what I’m doing. The other thing I struggled with in the book was trying to get to grips with the second generation – my parents’ generation. I could understand my era, I could understand my grandparents – who were these very idealistic, adventurous people – but I really couldn’t find a handle at first on the middle generation, those people who had all those expectations put on them, all that weight, and might well have struggled under it, but couldn’t protest. I think I found it, in the end, but this was just one of those books where I didn’t have a particularly easy time of it.

That sounds very annoying…

I don’t mean to moan. But you did ask! I’m really happy with the way it turned out, but I can never quite figure out why some books are hard. »Golgotha« (the third and final book of the trilogy, which just came out in English) – the whole first section of it, which is about an Austrian sort of cowboy who’s traversing 1882 Palestine during the Ottoman Empire, was just so much fun, in contrast. I blame Karl May! Who I sort of had in the back of my mind as I was writing that.

Karl May never actually visited the places he wrote about. What’s your approach to writing about places and times you haven’t personally experienced? And what’s your idea of truth in telling such stories – if that even matters at all?

I never visited 1882 Ottoman Palestine either, you’re right! So partly I did want to lean into that pulp feeling, that’s not entirely realistic – we have a cowboy, after all, a quest for gold, all these pocketbook tropes in there. I found myself using a lot of an old British travel guide from the period, which also fits in with the mindset – middle-class English people going on an all-inclusive holiday to the Holy Land, much as they’d go to Tenerife today! And complaining about the locals, the baksheesh, sending postcards home, and haggling over cheap trinkets in the market… I had no idea, for example, that it was very popular to get a tattoo when you got to Jerusalem! Some things never really change… So, I do a lot of research from contemporary writing from the era, maps, etc. And then I decide when I want to go and make stuff up in the margins. One of the books that inspired this is a very rare collection of early stories of Jewish settlement – the sort of gossip version that’s not in the history books! And I picked it up well over a decade ago and kept it until I could finally use it. So, the appearance of the comet in the skies of Jerusalem in 1882, I took that from it, for example. I try never to make stuff up, mostly because real history is always weirder and more compelling than anything I could make up.

Ruth seems to be one of the main threads running through the story. We see her as quite a cold and dark character. When I was reading, I kept picturing someone like Golda Meir or Ayn Rand. Were they, or anyone else, in your mind when you created her?

I don’t see her as cold! I think she’s hard, yes, but not cold! Though she gets quite dark, yes.

Haha, I get you. »Cold« might not be the best word, especially since we’re given so much background information that explains why she acts that way – all the sacrifices, all her losses, her ideals. I don’t want to spoil too much of the story, but at the end of the book we see her act in a way where her hard character really shifts into something else – that kind of idealistic thinking can make people act against some basic human principles.

Ruth’s ending is a small reference to a Hebrew writer I appreciate, called Yoram Kaniuk (who you might see Ruth reading at some point in the novel).

The German audience might know him most for his book about Yossi Harel and the Exodus…

Yes. He was of that founding generation who went on to write about, and interrogate quite harshly, the formation of Israel. I worked various obscure references to Hebrew literature in the book, and this is one of those. It seems inevitable for Ruth, though. You kind of think, with this kind of book, well – there are no good endings. Ha! As for Golda Meir – she does actually pop up here, I think (correct me if I’m wrong!), at least she does in both, »Maror« and »Golgotha«. She was an interesting character! I think there’s definitely that sort of strand of women who, in a way, had to do everything – they came to build this utopian society and to be equal to the men, but then also still had to look after the children, and carry guns. I grew up with the myth of it – from Hannah Szenes, who parachuted into occupied Europe to fight with the partisans, and was executed, or Sarah Aaronsohn, who spied for the British against the Turks, and was executed… okay, I am detecting a theme here.

When did you decide to make a trilogy out of it?

The whole idea of this trilogy, or at least some elements of it, came from, many years ago, really wanting to write a novel about Sarah Aaronsohn and that whole World War I Ottoman era, the NILI spy ring, and even though that never happened, it sort of fed into »Golgotha« a little bit.

The descriptions of life in the kibbutz are incredibly vivid and powerful. How much of that comes from your own experience? Did you draw on personal memories, or did you conduct research to capture it so precisely?

I grew up on a kibbutz, which has the advantage that I didn’t really have to make anything up. I just dialled up the misery and violence to like… eleven. It was like, okay, let’s take the worst possible kibbutz you can find and magnify that by a thousand. You know, I don’t think anyone did keep people locked up in a basement or had an epic shoot-em-up over government-sanctioned drug trafficking (though that’s actually based on a true story), but my brother read the book and said, well, I recognise the usual suspects. So no, I didn’t make much of it up. And some of it is based on stories my grandfather told me (like finding the two lost children, which Ruth does in the book) or running away and trying to get to the sea (which my dad really did when he was small). The weapons caches… we still had some that were never found, and we’d go every year with a metal detector to search for them. You can’t make this stuff up.

Haha, good for you! To me, the story feels like one about loss and the need to keep going. Was that an idea you consciously wanted to explore while writing »Adama«?

It occurred to me as I was writing it, that the characters, as much as they had any choices at all, only had two: to stay or to go. So, we see them struggling with that, and we see them making that choice, but in a way it’s a story they’re trapped in. Even if you leave, are you really free? But I didn’t have any conscious thought about what it would be, it was more of an attempt to write about these generations as truthfully as possible.

At the same time, the novel also feels like a very detailed portrayal of kibbutz life. Was writing it, in some way, a way for you to process your own experiences from that time?

It would be tempting to make that statement, but I really don’t think so, you know (of course, I would say that!). I had a weird relationship with the kibbutz – it was in many ways a sort of idyllic childhood, but I also knew from a very young age – and got into trouble for that! – that I had no intention of staying. Don’t ask me why! I never had any interest in ideology, and very little in nostalgia or sentimentality, but I was interested in the stories people tell about themselves – this sort of mythologising. That’s more what interested me in writing this. The mythology, versus what really happens.

Some of the scenes are extremely harsh – for example, when a kid shoots an adult. Was it your intention to include such dark, almost pulp-like imagery, or is that simply how you perceive life in that era?

Honestly, I didn’t make a lot of stuff up. You can find plenty of darkness without looking too far. The missing kids in the 1930s, 1940s… I could show you the newspaper clippings. The DP camps in Germany – my mother was born in one of those and spent the first two years of her life there. I never knew much about it, so the research into that was pretty eye-opening. Or the brothels during the British Mandate… I document stuff that just happens to be pretty dark.

Why did you choose a crime story as the framework to carry the larger narrative? What does the crime genre allow you to express that perhaps another form wouldn’t?

I think just because it is a history of crime. Which is another way of saying it’s really about morality. What is the right choice, or where is the line between right and wrong? And what I find fascinating about all these characters is that they all have a moral code of some sort, they all have a line – but that line can be really far in terms of doing bad things. You see it with Dov, when he goes chasing a killer in the middle of a mass displacement – it’s a ridiculous endeavour. That whole section’s based on a real war crime, incidentally – it was fascinating, following it through the yellowing pages of the newspapers, and amazing that it even got reported on back then.

By the end of the book, the reader gets a sense of why life in Israel – especially in the kibbutzim – is the way it is. It’s portrayed without romanticism, yet with a deep understanding of the people. At the same time, the country seems to be moving toward normalization, becoming more like any other state, while the great ideals begin to fade.

I doubt kibbutz life is very similar these days – what’s left of it. The communal children houses, all that stuff’s gone, lost in the ideological battles of the 1980s that I grew up through. It’s a snapshot of how things once were, maybe. And, again, a sort of magnification of that, to some extent.

Why did you choose to tell the trilogy in reverse order chronologically, from the present to the beginning, rather than the other way around?

As for the trilogy being told backwards: it’s a good question. It felt like it made sense, to start where we are and work our way to how we got here. But the funny thing is, now that »Golgotha« is completed (and will be out in German next year), theoretically, you can read the books forwards in time, starting in 1882 and ending in the 2000s. I’m really curious to see how that would feel! I think they would both work.

Now that your trilogy has been completed (though not yet released in German), what’s the next step? What did you learn about writing during your Karl May era?

I know it sounds crazy, but I’ve just come off the back of writing four serious, literary historical novels (»Maror«, »Adama«, »Golgotha«, plus »Six Lives«) that engage with and interrogate the real world and some of its darkness, and everything feels quite down right now, doesn’t it? So, just to confuse every publisher and bookseller out there, I set off to write a giant space opera novel instead. Ha! It’s just about having fun for a bit, which I think readers also quite want right now. I’m enjoying it! It’s huge and silly and I get to make everything up again! There are so many aliens and planets and things I have to make up, I get to blow up entire galaxies and just play around. And I have a small backlog of science fiction and fantasy books that sort of collected by now, so I’m hoping these all come out in the next two to three years in English. I had a very rough time, creatively, after I finished »A Man Lies Dreaming« (this hugely ambitious book where Adolf Hitler is a fallen-from-grace private detective in London, haunted by his loss – I am told it will never be published in Germany!), and really a long period where I couldn’t figure out how I could top that. Now, in contrast, I’m in a place where I have too many books I want to write. I want to follow »Six Lives« with another interconnected historical novel at some point, I still owe my publisher two books in my »Anti-Matter of Britain« series (I only wrote two out of four), and I’m tempted for a straight crime novel at some point, just for fun… I do seem to be drawn to either the far future or the past, which seem like two sides of the same coin. Plus, you know, my new children’s book, »Komm mit in die Zukunft«, just came out in Germany and I love the idea of doing a children’s book every few years. My first one – »Geheimagentin Candy und die Schokoladen-Mafia« – came out in 2018 in Germany. So yes, every few years sounds about right!

I’m breaking out in a sweat with so much output! Thank you for your time and your very, very delightful insights.

Link: https://www.suhrkamp.de/buch/lavie-tidhar-adama-t-9783518475164