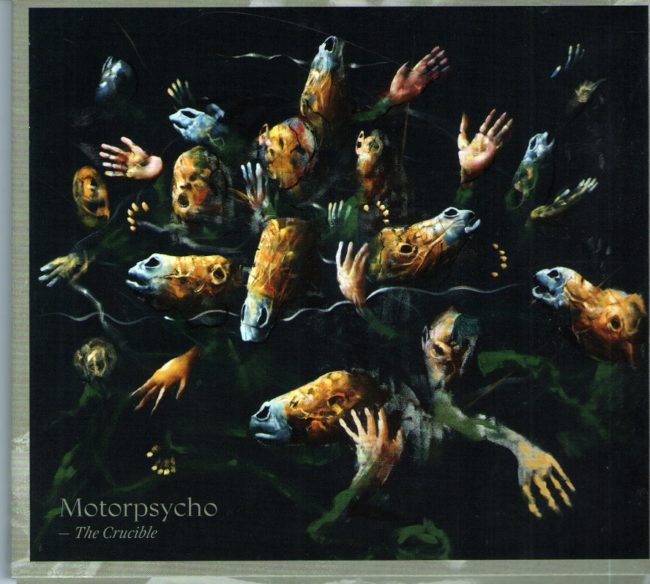

Mensch sucht ja heutzutage meist vergeblich nach Bands, die »die Zeit überdauern«, wie die Rolling Stones, die seit 180 Jahren ihr Ding machen und mehr oder weniger wertig abliefern. Doch den Pessimist*innen sei hiermit widersprochen: Es gibt diese Band doch noch und sie nennt sich Motorpsycho. Weniger konventionell als besagte Stones, doch nichtsdestotrotz machen sie seit unzähligen Jahren Musik nach dem Schema »Motorpsycho«, also irgendwo zwischen Psychedelic-Rock ohne Drogen, Prog-Rock ohne Zauberer und Elfen, Gitarren-Rock ohne Eierschaukel, Grunge ohne Selbsthass und so weiter hin und her mäandernd. Wie Van der Graaf Generator in weniger verkopft und mit mehr Sexyness. Und das konsistent, ohne Ausfälle. Mit ihrem neuen Wurf »The Crucible« (»Der Schmelztiegel«) machen Bent Sæther (Bass, Gesang) und Hans Magnus Ryan (Gitarre, Gesang) da weiter, wo der Eineinhalb-Stunden-Brocken »The Tower« aufgehört hat, diesmal etwas fokussierter und wieder mit dem neuen Schlagzeuger Tomas Järmyr (Zu, Werl). »The Crucible« nun besteht aus drei Songs und ist mit kaum 40 Minuten regelrecht kurz. Auf dem Opener »Psychotzar« hauen sie wie gewohnt mit ordentlich Foffo in die verzerrten Saiten, mit fast neun Minuten ein kurzer Einstieg, aber Herrgott, diese Riffs! Und das Riff am Ende von »Psychotzar«! Der zweite Song »Lux Aeterna« hat die liebreizenden Harmoniewechsel, die an Steven Wilson (bzw. dessen Porcupine Tree) erinnern – sogar sehr. In »The Crucible« verschweißen sie sogar Ideen von King Crimson (»One More Red Nightmare«) mit eigenen und verzwirnen sie in gewohnt ausufernden Jams. Legitim! Produziert von der Band selbst mit Hilfe von Andrew Sheps und Helge Sten (alias Deathprod). Es ist nicht nur interessant und schön, was sie immer wieder musikalisch Wertiges auf die Beine stellen, sondern auch, was Bent zu sagen hat:

skug: Your new and beautiful record is called »The Crucible«, and a crucible is something where lots of different things like ideas, cultures, ethnic groups etc. get/come together and something new emerges. Was this your intention?

Bent Sæther: Obviously, but in areas that the lyrics dealt with specifically. Let’s take the title track: Last year marked the centennial of the end of WW1 – probably the biggest cultural and political upheaval on a world scale ever – and this was a subject that triggered a lot of thoughts on the current situation. The fact that the Trump administration is disassembling the federal government and seemingly doing their best to undermine the rules that have controlled the modern western liberal democracies since then makes it pertinent to ask if we’re watching the first slide back to the values that WWs 1 and 2 contained and made untenable. Brexit, the Russian, Turkish and Venezuelan political trends, not to speak of the Saudi Arabian and Syrian situations. Or the ecology… this is important stuff and it’s real, and it’s happening right now. It felt like WW1 was a good example or metaphor for this theme, one that would match the size and ambition of the music, so we tried to make them go together. The lyrics are obviously literally about WW1, and as such closer to Steve Harris than Jon Anderson, but … there you go! The other two songs also deal with this: »Psychotzar« with the »big men« of politics in a literal sense, while »Lux Aeterna« addresses the subject more in a general sense, as a meditation on death. Since we know that what will be on the other side isn’t any better for most of us, how can we so recklessly throw away the value systems our elders fought and died for? Is the greed and need for personal gain so big that we’re willing to take chances with this stuff?

Your last album, »The Tower« came just after Trump’s election. The picture is quite clear. Can we see »The Crucible« as a more optimistic sequel that deals with the possibilities of the current state of the world?

»The Tower« was a reaction to the opening of that Pandora’s box, and mostly addressed the decency – or the lack of it – I felt was one of the key points around that situation. But it’s doomy shit for sure and the lyrics probably got a bit dark, indeed! I don’t know if »The Crucible« is any lighter in tone, or if the way these subjects are addressed is any different, but we’ve had two years of this kindergarten madness now and have had more time to see where it seems to take us. That definitely informed the lyrics. But I think they might be asking if this, too, is just another of those cycles that seem to govern all movement in the universe. Death might be, for sure, and wars seem to be something we never get tired of… I dunno. But yeah, same themes but further on, and probably not more optimistic.

»Lux Aeterna« has this Steven-Wilson-esque vibe, and the third track, with the upward-shifting of the riffs, reminds me – in a very nice way – of King Crimson’s »Lark’s Tongues in Aspic 2«. Was it intentional? And which recent artists do you consider as being influential to your music?

Oh, Steven Wilson? Really? I have to tell you that none of us ever listened to anything that gentleman ever did, except for some of those remixes he did of 70’s classics by Crimson or Tull or someone! I have no idea what he is about musically, so I have to plead the 5th on that one! But, yeah – musical mavericks from all eras are an inspiration, certainly King Crimson and other bands of that era is one, but also newer stuff and even older stuff: it seems to me that all the best stuff happens before things are formatted and labeled, so all the early stuff by anyone is usually what we find most interesting, since they hadn’t had any success yet, or »grown into themselves« if you like, and no-one had thought of it as »a thing«, it is between definitions and all its own. There is something magic about hearing bands or artists reaching for something, and that is what makes e.g. KC so inspiring – the constant reaching for the unknown. If there’s a »Larks Tongues« influence, it was not a conscious steal or anything, but we’ve listened a lot to Bartok’s string quartets over the last couple of years and that stuff rubs off…!

This is your second album with Tomas Järmyr, whose drumming is pretty forward-going and neat. Did you choose him to leave the psychedelic field and to focus more on that heavy and powerful guitar-rock style of your earlier releases?

Uhm… not really. We did – to our surprise – find that his style of drumming really suits our 90’s material really well, but we haven’t set out to do anything specific stylistically. Kenneth Kapstad is a lot busier than Tomas usually is, so Tomas’s drumming leaves more air in the music than what he did, something that gives it more grandeur and size I guess, but… we think of this as psychedelic more than heavy, albeit »psychedelic with muscles«: Psycho and Motor, and certainly relatable to earlier, quieter albums like »Here Be Monsters«. We move all over the map all the time, and it was the producers that chose these songs for the album, so it’s hard for us to see any trends like this from the material. I know that limiting the album to a single LP length was a conscious choice, and also, that the shorter, lighter songs felt insignificant in this context, so it felt right to leave those off this one. but coincidences, not a trend, I think.

The first time I heard your music in 2004 (»Timothy’s Monster«) I got struck by a rush of melancholy and I didn’t lose that feeling until today. Is it something typical nordic/Norwegian that runs through your music like a golden thread?

Perhaps? I have no idea why it sounds like it does, and I have to admit I listened way more to Kiss than Edvard Grieg in my formative years, but… we do have a hankering for melancholia and music that seems sincere (Nick Drake, The Cure, Dinosaur Jr, etc.), so that probably shows in our thing, too. We do agree that for something to feel real, you have to have all the colors of the spectrum. If you want a musical part to feel loud, you have to have something quiet, too, or else it just nulls itself out. For some of our music to feel as angry as it needs to, we have to have some melancholia in there too for the anger to feel real – and vice versa. Besides, there’s nothing quite like a sad song, is there?

After such a long time of touring and making music in the studio: How important are live concerts for your work in the studio?

We have learned that the album version of any given musical piece is an idealized draft of what feels like needs to be there to paint a clear picture. There is no such thing as a »definitive version« obtainable in that situation. So we try to nail an inspired take of the song with as much energy and fire and drama as we can, before we tart it up a bit – knowing full well all later versions we ever do will be different. To avoid frustration, we have embraced this, and try to relate to the songs like a jazz band would: as a key and a tempo and a feel for further musical explorations on a theme. Abstract speak this, but… that’s why we play music and don’t write books!