What is the spirit that subsumes such diverse artists as Sleep Museum and Blacklist under one label called Wierd? What are you taking into consideration when signing or releasing an artist, what are your criteria for music to be released on the Wierd label?

Pieter Schoolwerth: Above all the sounds of these bands are incredibly humanistic in their sensitivity, fragility, and directness – you can truly feel the hand of the artist behind the songs, something very much missing from most new pop music today. Nearly all of the bands on the label perform and record their music entirely live and unmediated – which is very different both from the multi-tracking and overdubbing of the 80s groups; as well as the cut, pasted, and clicked-and-dragged-to-oblivion laptop pop of the electroclash, indie pop and electronica groups of the past 5-10 or so years. The new Wierd label sound is emotionally similar to the sound of the 80s cold wave and minimal electronics groups but is much more modern and has arisen out of a different set of concerns or challenges the bands face. Wierd has released over 150 tracks by artists ranging from industrial/noise to fast and furious minimal synth, to guitar-driven wave informed by classic American rock and roll and UK post-punk. But I would say all are tied together by their emotional resonance, which is a very affirmative sense of melancholy, backed by an aggressive, life-affirming spirit of resistance. Whereas the 80s groups responded to implicit cold, colourless alienation of the repressive regimes of Reagan-Thatcher-era politics and culture, today’s groups I think express a similar frustration responding to what I call »the culture of isolation« – some of the more problematic attitudes that have been created by the negative effects that internet »culture« have had on new music and art.

In the world in general, and New York in particular, in a time when people are becoming more and more isolated every day by the internet, alone at their computers and staring at the tiny, sad glowing screens in their cellular hands, it only makes sense to me that we are all feeling a slight sense of loneliness and (hopefully) the desire for connection with others which is slowly slipping away year after year. This is one of the predominant feelings of the Wierd world – an affirmative sense of humanistic longing for true human connection conveyed through emotionally melancholic sounds. But simultaneously there is a very aggressive celebratory DIY punk spirit and true resistance to this isolation, making it very clear we all refuse to give up on the world, as brutally abstract as it all may be. One common thread behind the sound of the new cold wave, I think, is a true sensitivity and directness – you can still hear the human spirit alive behind the music. Most indie-savvy engineers and producers now hide artists behind a wall of vacuous effects, distortion and radically blown out vulgar laptop cut and paste production values. If you even get to the point where you hear a human voice alive in the song, the lyrical content of nearly all »indie«-oriented music is post-ironic. In the same way that vocal FX create an impenetrable wall between the performer and listener in the studio, irony creates vast, empty distance in lyrics and thus protects artists from being vulnerable, which is a large part of what making any art is all about in my opinion, communicating with another human being…and this is truly and absolutely …Very Rare.

In the world in general, and New York in particular, in a time when people are becoming more and more isolated every day by the internet, alone at their computers and staring at the tiny, sad glowing screens in their cellular hands, it only makes sense to me that we are all feeling a slight sense of loneliness and (hopefully) the desire for connection with others which is slowly slipping away year after year. This is one of the predominant feelings of the Wierd world – an affirmative sense of humanistic longing for true human connection conveyed through emotionally melancholic sounds. But simultaneously there is a very aggressive celebratory DIY punk spirit and true resistance to this isolation, making it very clear we all refuse to give up on the world, as brutally abstract as it all may be. One common thread behind the sound of the new cold wave, I think, is a true sensitivity and directness – you can still hear the human spirit alive behind the music. Most indie-savvy engineers and producers now hide artists behind a wall of vacuous effects, distortion and radically blown out vulgar laptop cut and paste production values. If you even get to the point where you hear a human voice alive in the song, the lyrical content of nearly all »indie«-oriented music is post-ironic. In the same way that vocal FX create an impenetrable wall between the performer and listener in the studio, irony creates vast, empty distance in lyrics and thus protects artists from being vulnerable, which is a large part of what making any art is all about in my opinion, communicating with another human being…and this is truly and absolutely …Very Rare.

Please give us a short version of the history of Wierd Records.

PS: Wierd began as a casual weekly gathering of artists, musicians, writers, designers and the like spinning our favourite records at a tiny dive bar under the Williamsburg Bridge in Brooklyn in 2003. I have long been a collector of classic minimal electronic, cold wave, and industrial records and week after week the crowds began to grow, and many new young bands were born of the spirit of the music we were playing late into the cold night each week. Eventually we began holding larger parties once a month in various clubs, warehouses, and galleries for the new groups who hung out at the party to perform live and slowly a new music scene and wildly vibrant social community was very organically born in the process. After a few months of these roaming live events I remember one night spinning about a solid hour of new music given to me on CDrs in the past month by my friends dancing before me under the foggy flickering beams off the disco ball in the room, and I started laughing to myself as I realized suddenly that we were all slowly building a whole amazing musical world together! At that moment Sean McBride from Martial Canterel walked over to me at the DJ both and handed me a CD demo for a track which was later released on his debut LP – the icy minimal electronic killer »Nightfall in Camp« … I slid it into the frozen cold airwaves in the room and chills shot up my spine … the inspiration behind WIERD Records was born at that precise moment.

By 2006 the Wierd had outgrown its Brookyn home and following the release of the first »Wierd Compilation« (3 LPs, 7″ + 32 page book) we decided to move the party to a new bar in the city Home Sweet Home where our friends The Hunt were bartending; so I brought in my screwgun, a pile of plywood and a PA system and in a few hours work we had a great new live music venue to take over so a different Wierd-related band could perform live at the party each week to truly unify the label and party and give the community a geographically consistent home base. It was at this time that a whole new wave of young artists discovered the Wierd, including Samuel Kklovenhoof and Shawn NoEQ from Led er Est who have provided Wierd with an intense new shot of energy. Led er Est’s music draws from a very different musical tradition than Martial Canterel. Xeno & Oaklander, or Blacklist. Sam and Shawn have long been fans of German Electronic music of the 60s and 70s as well as early house and Italo Disco, and from these worlds they have formed a very unique new sound that is truly their own. We’ve now done over 100 live performances at the weekly Wierd Party since 2007 and its going stronger and Wierder than ever!

One could think of the infamous Some Bizarre label when looking at your work – do you see any link? What are the challenges for a small, independent record label in 2010?

PS: All of us at Wierd grew up listening to the great independent record labels of the 80s and 90s such as 4AD, Factory, Les Disques Du Crépuscule, Independent Project, Wax Trax, Mute, Some Bizarre etc. which we all love. But to be honest all of those labels had it very easy in comparison to what a small community and label such as Wierd has to face today. In the 80s and 90s before the collapse of the music industry at the »hands« of the internet, iTunes, torrents and alike, the dialectic in music was »the big major label versus the small indie label«. Today major labels have all but disappeared and now the battle to survive is very different, and young bands are no longer able to sell tens of thousands of physical releases such as the 80s indie bands were that thus allowed them to tour, prosper, continue, survive and develop. Today almost all young people have grown up with a very problematic ethics that says music is free to steal on the web and this has made it infinitely more difficult for a small label to survive,

and bands to grow and mature slowly over several albums and years. As I mentioned before the struggle for bands and small labels to survive in 2010 is to navigate and above all RESIST the negative effects that internet »culture« has had on new music and art.

Xeno And Oaklander live in Berlin / Photo: Diana Daia

Of course the web has helped music in many ways – every day my mailbox is jam packed with amazing new tracks from bands from all over the world and I have made countless new friends and allies through MySpace and met many bands that discover the Wierd Records website. But I feel very strongly that the fantasy that true community and subculture can be built through activities on the Internet alone has proven to be an absolute fucking failure. The Internet’s intrusion into the music industry has led to a new culture of nihilistic amateurism. The »hurry up and get the album out«-blog-hype-backlash-break-up chain of events I see in band after band nowadays is incredibly depressing, and for musicians it takes their attention away from the creative process, creating a tremendously distracting pressure that has no other effect than watering down the music itself. In the 80s and 90s the struggle of a new, young band or record label was against the oppressive forces of the »major label music industry«, but today in a world where this industry has all but dissolved at the »hands« of the brutal isolationist abstraction inherent in the logic of the web, the web itself is the force to contend with … this is the new battlefield for independent artists and musicians.

How do you explain the big resonance in the US art scene? Your artists have been featured on the Art Basel Miami in 2009, playing in front of almost a thousand people …

PS: I make my living as a figurative painter which I have been doing professionally here in New York since I moved here from Los Angeles in the early 90s. My daily life in the studio is quite isolating as I sit alone before a big blank canvas all day long, year after year. Since I was a teenager in the mid-80s music has always been an affirmative antidote to this quiet, isolated world as it forces me to be amongst other people. I have always loved playing in bands, DJing and hosting big debauched parties as a nice way to balance out my life and meet thousands of amazingly talented artists in the Brooklyn night. The subject of my paintings has long been the struggle to paint people and their physical bodies and keep »the human« in art alive in a time when the body is becoming less and less important; as the internet, cell phones, television and other forms of new media make us more and more alone and separate and we exist more purely on screens to others than in »reality«. And using music to bring people together in real space and time is in a way exactly what I am trying to do on the canvas – keep the social world of the physical body alive and full of pleasure … so in a way I spend all day in my studio »making people« on the canvas, and at night they all come out to play and celebrate the Wierd World!

When I have an exhibition I often invite stage an extravagant musical event in conjunction with the opening as we did recently at Art Basel, Miami and will do again in France for the opening of my new exhibition at Galerie Nathalie Obadia in Paris. Staging concerts in contexts outside those of the often tired, banal clubs and »stages« of the pop music industry can be great for the artists and provide many new opportunities such as unusual venues, access to extravagant theatrics, older and very eccentric, visually-oriented critiques of the performances etc., that are unavailable in the commercial pop world.

Is New York itself to be seen as a »precondition« for the success of Wierd? – Why do you think New York is connecting so strongly with the sounds of Cold Wave and Minimal Electronic music right now and what would you say it is that attracted you to these sounds?

PS: Since 2003 we have all been working together here in Brooklyn to lay the groundwork for a true community in the flesh of musicians and DJs that believe in, support, share ideas, and protect each other from the creatively oppressive forces of today’s anxiety-fueled music industry. Xeno & Oaklander, Blacklist, Led Er Est and Martial Canterel just to name a few Wierd artists are so incredible now precisely because they have each performed live so many times at the countless parties all of us have produced together as Wierd over the past five years and each have had the time and space to focus, carefully hone their craft, and write songs. So for the past few years building this environment that allows musicians this new social space to breathe and develop has been our focus, and the next era for Wierd has just recently commenced this past November with a series of new solo artist releases beginning with the Xeno &Oaklander and Led Er Est albums. There are many more releases in the works coming this spring and summer!

Cold Wave and Minimal Electronic music in its first wave was almost entirely a continental European phenomena in the early 80s, but because almost all of the groups sang in their native languages of French, German, Italian and Dutch few of these groups were on labels with distribution and were largely all located outside of metropolitan areas in small towns and suburbs, and thus were never heard in the US or UK. So this massive world of thousands of groups has long been overlooked and sadly forgotten. I’ve made it my mission to reveal this secret history to Americans over the past 5 years … and slowly it is finally coming to life before our eyes. Cold Wave was a guitar-driven form of »Wave Music« that was quite informed by the icy razor blade guitar sound and high-end heavy drumtracking of producer Martin Hannet at the Factory Records label in Manchester from 1978-1980. The Minimal Electronic bands made music with a similar emotional resonance but used analogue synthesizers, sequencers and drum machines very inspired by the early industrial groups such as Throbbing Gristle, SPK, and Cabaret Voltaire, as well as the German electronic bands of the 60s and 70s such as Can, Neu! and Faust.

Sean McBride: At the end of the 90s music had become quite disembodied; the widespread use of the computer/lap-top as both a sound source and playback device for live performance coupled with an ethics of technological speed – there are certain parallels with the advancement of military might – left me wanting something more visceral, more alive, resistant. Having always had an interest in analogue synthesizers, and having grown up listening to some of the slightly more above ground groups who were using synthesizers and who were reflecting on the breakdown of the state, the impossibility of love, the shifting nature of human interaction; I found this was the perfect site to initiate a new music project where I could dedicate myself to a limited array of physical instruments and ultimately create something fresh from the ashes of the mostly forgotten 80s underground. There were individuals like Baard, John Bender and Ludo Camberlin (A Blaze Colour) – to name a few – who were making music which I felt was like a light shining into the fo

Sean McBride: At the end of the 90s music had become quite disembodied; the widespread use of the computer/lap-top as both a sound source and playback device for live performance coupled with an ethics of technological speed – there are certain parallels with the advancement of military might – left me wanting something more visceral, more alive, resistant. Having always had an interest in analogue synthesizers, and having grown up listening to some of the slightly more above ground groups who were using synthesizers and who were reflecting on the breakdown of the state, the impossibility of love, the shifting nature of human interaction; I found this was the perfect site to initiate a new music project where I could dedicate myself to a limited array of physical instruments and ultimately create something fresh from the ashes of the mostly forgotten 80s underground. There were individuals like Baard, John Bender and Ludo Camberlin (A Blaze Colour) – to name a few – who were making music which I felt was like a light shining into the fo

g, disappearing when the fog settled. It could not be easily classified, there were no rules, there was no particular identity to it, just some people the world over who, with their synths and rhythm devices, were trying to express themselves in an apathetic world.

Liz Wendelbo: Having played in garage punk bands in the past, the immediacy of analogue synthesizers appealed to me – their temperamental nature, their raw electricity one can shape and bend.

PS: I have never thought of the sounds of the Wierd bands as simply a revival of these groups‘ sounds, as these long-expired Cold and Minimal European groups we all love such as Twilight Ritual, Asylum Party, Opera de Nuit, Martin Dupont etc. were never heard the first time around here. I have always loved classic sound of the »Vague Froide« bands in France in particular (later translated as »Cold Wave« and where the movement received its name in 1980), for to an English speaking fan as myself I hear the beautifully flowing sound of the French language truly as another instrument that flows and soars through the airwaves; that is so appropriately suited to convey the emotion of melancholy as the great modern poets in 19th century Paris such as Mallarme, Valery, and Baudelaire did so similarly. In the world in general, and New York in particular, in a time when people are more and more becoming isolated alone all day by the internet at their computers and staring at the little glowing screens in their cellular hands, it only makes sense to me we are all feeling a slight sense of loneliness and longing for connection with others… this is one of the predominant feelings of the Wierd world – a sense of humanistic longing for true human connection conveyed through melancholic sounds, but simultaneously a very aggressive celebratory spirit and true resistance to this isolation, making very clear we all refuse to give up on it all and keep the socially vibrant Wierd late night social NYC world alive and well – ladies and gentlemen get off your asses, it’s time to dance!

SM: Also I would have to say that today in Brooklyn there is more of a spirit of community as many of us share an affinity for minimal electronics and are revisiting thought-to-be outdated methods of music making. But I wouldn’t limit the question to just groups popping up in Brooklyn, as there are very integral parts of the community worldwide. I think the chief difference between what we saw in many 80s performers, for the most part, was the synthesizer’s function as a tool of future-making, like the aforementioned difficulties with computers today, the politics of advanced technology played a central role for many groups, especially themes of Artificial Intelligence, Cybernetics, Robotics, and Cryogenics. These days we are seeing more human and perhaps mundane expressions of day to day living – such as memories from a lost past, love betrayed, political tribulations …

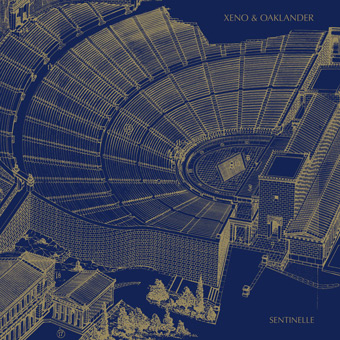

Xeno & Oaklander’s new record features the Acropolis of Athens in its artwork, a recent Wierd-event was called »The Pleasures of Xanten« (referring to the birthplace of Siegfried from the »Nibelungen«). Can you explain your approach to politically charged historic and mythological topoi in just a few words?

LW: The Acropolis is a collection of monuments that we like to explore in our artwork – the »Sentinelle« album cover features the main amphitheatre, and the »Vigils« Cdr features a temple adjacent to it. Our fantasized concept is that our total oeuvre could eventually survey the whole map – all records put together would constitute the whole Acropolis in order to form a complete collection, contained within the walls of this archeological site.

LW: The Acropolis is a collection of monuments that we like to explore in our artwork – the »Sentinelle« album cover features the main amphitheatre, and the »Vigils« Cdr features a temple adjacent to it. Our fantasized concept is that our total oeuvre could eventually survey the whole map – all records put together would constitute the whole Acropolis in order to form a complete collection, contained within the walls of this archeological site.

SM: In 2003, my friend (Epee du Bois) and I were travelling through Germany and for a few days were staying with Rainer Franke who runs the Genetic label; Rainer, having to attend to some other business, thought we might enjoy an afternoon at the »Archäologischer Park Xanten« which wasn’t far from his house. Having just come from Pompeii, we found the site quite peculiar with its partial recreation of the Roman Colonia Ulpia Traiana but in ruins. This idea of rehabilitating an antecedent moment in history but building into it its own undoing/downfall was interesting and has since provided a kind of figuration and metaphor conveying and problematizing the musical universe we inhabit. So I made a small label called »Xanten Records«, the »pleasures« of which simply refer to a meeting or pairing of the musicians involved – Epee du Bois, Sleep Museum, Staccato du Mal, Opus Fini, Alex Waterman, Martial Canterel and us of course.

There is not much political charge to an illustration of a Greek amphitheatre in the US, however I am aware of the dissent stirred by the use of pre-Christian symbols and motifs, especially in Germany.

What is your artistic and personal opinion on the ever-controversial Neo-folk discourse and the reinterpretation of signs? Can there be »l’art pour l’art«?

SM: The about-face political change made by some of the early Neo-folk groups from a pro-worker Leftist punk orientation to an esoteric, occult Right-wing position was a self-conscious affront to the ever-growing commodification of Punk music, it was a strategic move to maintaining a hermetic underground and allowing the debate to thrive. The image and appearance of Neo-folk is easily absorbed into mainstream and normative modes of dissemination, which results in confusion in relation to its initial objective as a critical strategy.

In line with Walter Benjamin, »art for art« takes on an almost theological dimension whereby the subject and/or the social function is negated in favour of some idea of perfect form, an idea of purity which can lead dangerously close to art’s utilization as a social controller or as a mass conscience manipulator. There have to be fissures, openings into which the performer and the audience may enter and reflect – some kind of quasi porous membrane, like that of an organic cell, which can simultaneously uptake and expel meaning and significance. We would like to see the human remain in art (music.)

Martial Canterel borrowed his artist name from a scientist and inventor in Raymond Roussel’s novel »Locus Solus«. How much does this role actually reflect Sean’s artistic work?

SM: Hitherto 2003, I was using the name Moravagine, a psychopath noble who travels the world helping to foment revolution whilst eviscerating little girls, taken from the Blaise Cendrars‘ novel of the same name. Having found the name was already being used for an Italian Punk project I chose Martial Canterel, another early 20th century protagonist from Roussel’s Locus Solus. I do not regard myself as an inventor or a scientist, however there are some essences which I imagine correlate. For instance, my studio has been known to take on the appearance of some alchemical lab from the early 1970s not unlike Canterel’s Locus Solus estate. But what interested me more than the character himself was the modular and at times aleatoric nature of the narrative constantly deviating, (de)evolving from one explanation to another. The lyrics of MC also take on a dimension of chance. In devising a cadence or staccato order to the voice, I then have to constrain a text which fits into this pre-established array. Another feature of Roussel’s work which I appreciated was his »Nouvelles Impressions d’Afrique« where he hired a detective to deliver terse phrases from his book to Henri Zo (at the time a well known illustrator and pa

inter) who in turn created these very mundane illustrations to be used in the book, without the two ever having met.

Do you sense a particular interest in media like vinyl or tapes when it comes to the target audience of Cold Wave music? Are your extensive releases featuring artwork and page-long booklets an answer to today’s download culture?

SM: Of course there is a great interest in physical media as the abstraction of contemporary music as meagre ten second ring tones, disembodied albums, and everything at once at the end of one’s fingers has lead increasingly to a new form of dehumanization, which is rarely checked, as the next and newest processor or gizmo will only accelerate one’s ability to do the aforementioned faster. I can’t account for »Cold Wave« audiences, but in New York there is a renewed relevance to vinyl albums with booklets, original artwork, lyric sheets, to cassettes which were made by the artist in his or her home for next to nothing, even to CDr’s with scrawled marker titles. There is at least some personal exchange with physical media, even if mediated by a store.

SM: Of course there is a great interest in physical media as the abstraction of contemporary music as meagre ten second ring tones, disembodied albums, and everything at once at the end of one’s fingers has lead increasingly to a new form of dehumanization, which is rarely checked, as the next and newest processor or gizmo will only accelerate one’s ability to do the aforementioned faster. I can’t account for »Cold Wave« audiences, but in New York there is a renewed relevance to vinyl albums with booklets, original artwork, lyric sheets, to cassettes which were made by the artist in his or her home for next to nothing, even to CDr’s with scrawled marker titles. There is at least some personal exchange with physical media, even if mediated by a store.

Word has it that you own a huge personal collection of rare and precious releases. What is the act of collecting to you, and how does it influence your views on the music happening today? Will you ever reach the end of that deep well of forgotten sounds?

PS: Many of the artists and DJs in the Wierd world have a vast array of very rare musical releases, and I feel this has above all created an awareness of history, especially in European popular music that has productively informed what we all do, and has allowed an awareness of many sounds and obscure musical scenes in the past that may have been overlooked by others. The Wierd community began as I said as a DJ party where a group of us simply played our favourite records from the past, and out of the collective sounds that we were hearing from each other a new modern sound emerged very organically, from digesting these many rich, historically overlooked incredible artists.

Today however, with perhaps 30-50 bands now in Brooklyn alive and well and handing me new songs on CDr’s to spin at the party every week, my DJ sets are 80% new music, and I have come to have a very cautious attitude about »collecting«, and in particular the detrimental effects record collectors can have on new music. Record collecting has historically been a very middle class, middle-aged, white male hetero-sexual machismo-oriented enterprise founded above all on the egocentric control of obscure historical information. This, as well as the politics of distribution in pop music since the 80s (bands should sing in English, live in metropolitan areas etc. etc.) has functioned to keep so much great, unknown music precisely that – obscure, hidden, and sadly and tragically unknown. So my attitude as a collector has always been precisely the opposite – to »collect« only in order to share and expose the music that is great and merits recognition to young people and artists and those who cannot afford to buy it on eBay and the like, so as many people as possible will enjoy and be inspired by it; not to selfishly hoard, hide, and keep it to myself as so many collectors have always done.

Just out of personal curiosity – do you own (or if not, know) any (rare) Austrian releases?

SM & LW: Monoton’s record from 1980 »Monotonprodukt 02«, especially the song »Ein Wort«, and Leider Keine Millionäre’s »Was Zählt« EP from 1982.

PS: I wish I could say I knew of more Austrian music. I grew up in the late 80s and 90s as a huge fan of industrial and experimental electronic music and I was always a huge fan and collected the great Syntactic and Klanggalerie labels which released so many great tapes, CDs and records its impossible to list them all here. Apart from these fantastic labels, I would say the movements in the visual arts have always greatly impacted me – particularly the Vienna Actionists such as Hermann Nitsch, Otto Mühl and Rudolf Schwarzkogler … and of course as a younger artist the Symbolist movement in Vienna around the turn of the century, particularly the artists centred around the Vienna Secession have always been particularly inspiring.

Where do you see the boundaries of using analogue machines in new music? When or where do its possibilities to express come to an end?

LW: The boundaries in contemporary analogue music are what define it – the limits are set by the gear itself, one’s two hands, and by the fact that the gear is played live, the songs composed in one go. So in that sense our particular approach to minimal electronics allows for endless expression and concepts within a prescribed boundary. There is freedom in the minimum.

PS: I really agree with Liz and feel that in a day and age where most sounds generated in pop music come from anonymous producers simply manipulating a few computer programs, and removing the human voice via Autotune and the many technological devices that »abstract« the human presence from new music, analogue synthesizers provide a much needed new »ground«; on which to produce music which can function as a sort of clearly defined »restraining system«, in which all the terms are clear, and there are limits to what the artist can and cannot do sonically. All of which ultimately function to retain the human visceral presence in both live performance and recording.

Can you give us a small hint on what to expect next from Wierd?

PS: This spring and summer will see the debut LPs from our beloved cold guitar wave friends from France, Frank (just Frank), frozen hot Quebequois minimal electronics from Automelodi from Montreal, the debut LP’s from Brooklyn’s Epée du Bois, and Frank Alpine from Los Angeles, and of course the long-awaited first new LP from Martial Canterel in over 3 years! Xeno & Oaklander will embark on their first full-scale 20 date UK/European tour supported by both Frank (just Frank) and Led Er Est in April. And if I am still alive after all this I hope to get the epic box set »The Wierd Compilation Volume III« out by the end of summer …Very Rare.

(Nathan Clemence / redaction web)