The film opens with Charlie Megira at his guitar, playing »Heart and Soul« by Joy Division. And this scene is as beautiful as it is promising. His life has some of the tragedy of Ian Curtis, and an off-screen statement underscores this impression: »You have to understand: This activity is not meant to make your life easier. If we talk about rock’n’roll, it’s not meant to make your life better. What do you think it is meant for?« The journey of Abudraham began in Beit She’an, in Tel Aviv he became the person he would embody until shortly before his end: Charlie Megira. After a stopover in the US, he drifted back to the continent, to Berlin, where he took his own life in 2016.

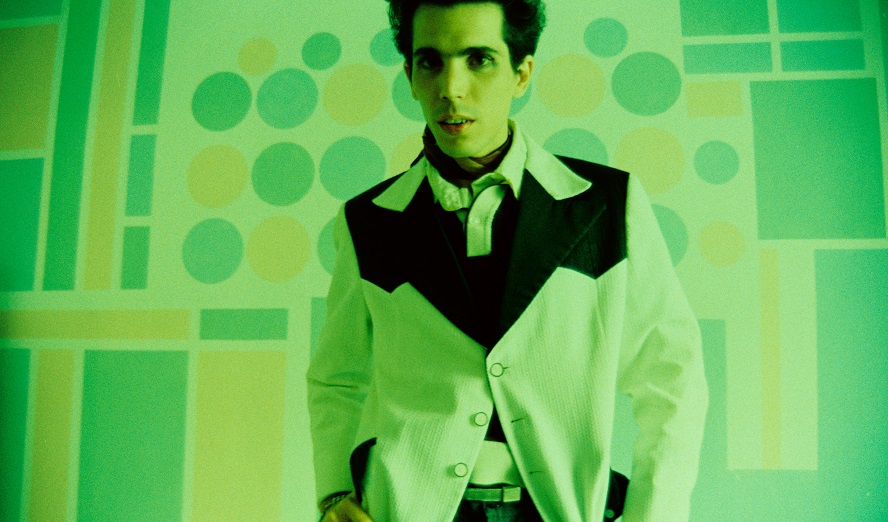

The young man with a dubious past did not become the guitarist and artist he was to be for about 24 years of his life until he was 20. Influenced by the style of Elvis Presley, Jim Jarmusch and Roberto Benigni, after a trial with the band »The Shnek« (1994–1997), he started his career in 2001 with »Da Abtomatic Meisterzinger Mambo Chic«, a mélange of bittersweet, melancholic lo-fi surf rock and rockabilly – his first and only real »solo record« (technically, but all his albums were actually »his« albums). Three years later he released »Hefker Girl«, the first of his two albums, his sound had evolved over the years into raw, melodic post-punk with American goth rock elements. The influence of 1980s’ Berlin, Blixa Bargeld and Nick Cave and their ilk is unmistakable and audible. Hefker Girl was Michal Kahan, who played the guitar in both albums, »Rock-N-Roll Fragments« (2003) and »Charlie Megira und Hefker Girl« (2006).

In 2009 »Love Police« (Michal Kahan switched to drums now) saw the light of day, his project with The Modern Dance Club, the punkiest, hardest of his albums with a whole 31 songs and another sonic break from his previous style. In 2013 he was part of Ari Folman’s Film »The Congress«. Along with Max Richter, he was responsible for the soundtrack, plus he even made an appearance as a cartoon character. Between 2013 and 2015 he released two albums as Charlie Megira and The Beit She’an Valley Hillbillies, »The End of Teenage« and »Boom Chaka Boom Boom«, with which he musically returned to his own rockabilly roots.

Megira’s career came to a »late climax« with a successful tour through the US. Then he met Julian Casablancas, with whom he played concerts in Europe – and who offered him a record contract. Unfortunately, this was never to come to fruition for unexplained reasons. After nine months in the States, he moved to Berlin to work as a cook, as he had done during his time in the Israeli army. He played a few more gigs, including some in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. On November 5, 2016, Gabriel Abudraham was found dead in his Berlin apartment, where he lived with his wife and 4 1/2-year-old son. People who had the pleasure to meet him in one of his favorite bars in Berlin remember him as a music-enthusiast and a very warm-hearted man. Which is in line with the man presented in the documentary.

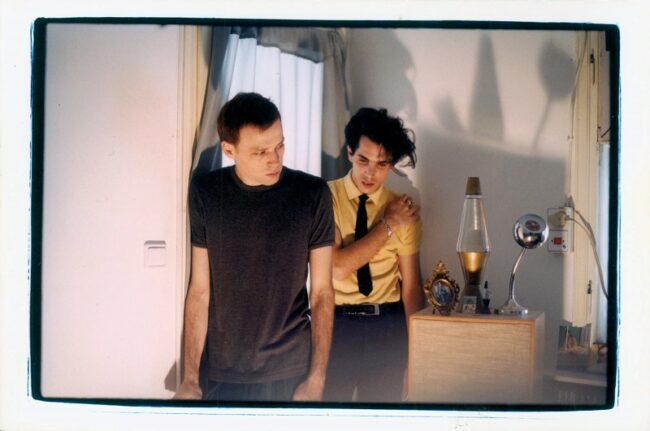

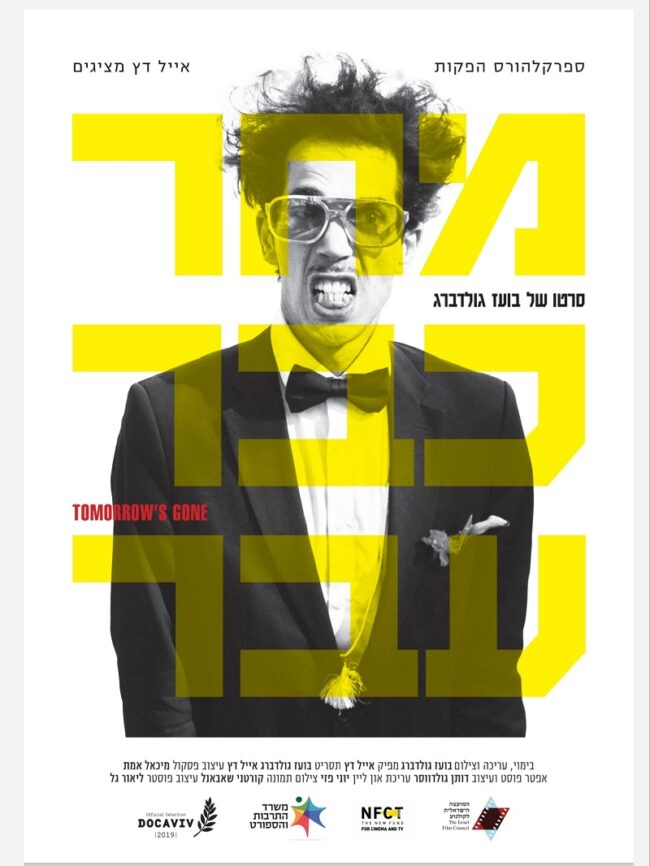

Boaz Goldberg, artist, music journalist and close friend of Charlie Megira, realized early on what a special person he is accompanying and began to film his life. It is because of this personal closeness that »Tomorrow’s Gone« manages to paint such a sensitive and genuine picture of Megira, always from the point of view of Goldberg, of course, a longtime friend and admirer. That the death of Megira does not mean the end of his music, is shown among others by the story of Valentin P. Monnereau, who as Danny Monroe resurrects the spirit of Charlie Megira and performs his pieces, even in Hebrew.

skug: When did you realize that you had to start filming Charlie Megira?

Boaz Goldberg: It happened around twenty years ago. It was at a time in my life when I felt a bit stuck. I quit playing the guitar, then quit the bass guitar, and then quit cinema studies. I still DJ’d everywhere I could, but I was looking for something more dramatic, a musical creation that would stay forever. A year or two before that, Charlie encouraged me to make a movie. So when I realized he was growing and something very special and unique was happening there, I felt I just must capture and document this rock’n’roll phenomenon.

So it was actually Charlie himself, who at the beginning of his career as Megira already had a documentary in mind?

No, he never told me to start a documentary about him. He was encouraging me generally, giving me ideas about going DIY. After about two years I had it in mind to start filming him for a documentary, and he was very positive, »sliding on it«, as we say here.

How did you two meet in the first place?

We met as early as 1995, through two mutual friends of mine. The scene was very small, and anyone who was into rock’n’roll counterculture was known to each other. First, I read a small gig review published in a local Tel Avivian newspaper about Gabi’s little band back then, The Shnek. I was curious about it. Then, a friend of mine, Dan Shadur, started playing bass with The Shnek, and one evening he offered me to join him for their rehearsal. Me and Gabi immediately started chatting about Johnny Thunders and The New York Dolls. Mind you, in 1995 it was like finding someone who speaks the same rare language as you. He was extremely introverted but with maximum style and magic. You could feel that he was hundred percent into it. Afterwards, when I visited his flat for the first time, he showed me how to play a song by an Israeli cult band called The Top-Hat Carriers (Nos-eiy Ha-migbaat), and asked me to show him how to play a song of a band I played in back then, »Cnaque / Pop«, then he played some crazy funky records of James Brown and Frank Zappa. I could see he was actually very versatile in his tastes and concepts. It was pretty rare in those days, to be all over the place. He was fascinating.

And how did the friendship go then?

There was never any »end« to our friendship or any argument. We never fell out. It was just that prosaic thing you see a lot in life and in friendships – for all kinds of reasons each of us took his own route. Also, it was only natural that when Charlie became the boyfriend and musical partner of my ex, Michal Kahan, something changed. It would be bizarre if it didn’t. We still met once in a while. For example, I remember how he helped me around 2008, when I was in an emotional mess. Or a year later I bumped into him in a small empty street at noon. We sat for coffee, he gave me a vinyl copy of »Love Police«, which just came out on a Hamburg label, and told me all about the first European tour. Then, I was grateful when he helped me with the guitar set-up into the mixer. Back then I was heavily into noise drones and experimented with it. We were never best friends again like we used to be, but when we met … we always had a lot to talk about. Also, when I was a rock journalist for more than a decade, I tried writing about him and mentioning him as much as I could.

And when he left for Berlin, how were things between you?

When Charlie left for Berlin, I had a full-time commitment owning a small bar in Tel Aviv, so that took most of my attention, that I can tell you from my side. Still, once in a while Charlie liked some drawings I posted on Facebook, and if you look at Charlie Megira’s Facebook page, you can see that in 2015 he shared a photo of us together from the The Lost Boys (Na-arey Ha-hefker) days, our little duo we had together. Nevertheless, I think the fact that we became ex-best-friends made my film much more emotional and warm, and probably more interesting. It gives the film a melancholic atmosphere, which I think is essential for a rock’n’roll piece of art. In my opinion, generally in art, when you’re making a portrait of someone, a certain distance is necessary. It kind of reminds me of that phrase we have in Hebrew: »Far from eyesight – close to the heart«.

How was playing with him?

It was really inspiring. At that time, in 2000, I hadn’t played for about three years. Gabi was patient, and I followed his rhythm lines. We went through songs from his first album, and focused on one of them: »Yesterday, Today & Tomorrow«. I was in charge of musically producing that song, and it came out really magical, I think. You’ll be surprised to hear that the original mix was done by DJ Guy Gerber, nowadays a famous mega-DJ. He was a mutual friend back then. I got it on cassette tape, it’s not the mix that Charlie chose to be on the album. It also has more piano by Shy Nobleman, a power pop singer friend we brought to play, and the percussions by the great drummer Ram Gabay of The Fluorescents sound louder. Our duo was supposed to be something very melodic like The Everly Brothers, but more raunchy. It was 2000, the electronic club scene was blooming and exploding, and rock’n’roll was a bit neglected back then. It was even before The Strokes’ first album. So the feeling was also a feeling of being on a mission. In 2017, while working on the film, I re-recorded one of our songs, »Pink World«, which was really lost. You can hear it on all the digital platforms under the album title »Headless Elvis« by ZICO, which is my nickname. From that recording, which I eventually didn’t edit into the film, I think you can catch a bit of that dreamy atmosphere we had.

It seems the scene in Tel Aviv is very well connected – or just very small?

Nowadays it’s very well connected and that’s not because it’s small. Back then, the scene was very small and well connected, mainly in-house, I mean, more inside Israel. Nowadays it’s well connected both inside and outside. Globalization has some pros and cons. It’s blurring each country’s individual tastes and language, but at least the connections became very easy. Like we’re talking now and exchanging ideas.

How did he react to being filmed?

Charlie was really into it – totally into it! I think the shots speak for themselves. You can see how intimate he was in that long exclusive interview I had with him, or in that scene when I come before the gig, when he and the band are getting set up with all the little chats in his little flat. It’s very precious, because the film would be totally different without it. It became, as I say, »the main boulevard« of the film, and I am very proud of it. It’s actually the only serious video interview with Charlie Megira in existence.

Where did he come from, family-wise?

Gabi was born in the rural north of Israel, in the small city of Beit She’an. Then his family moved twice, to places nearby. As far as I know, and from my experience, I can say his family are very good, warm-hearted, and, most importantly, moral people. He had an aunt who adopted many children, and I know he loved that aunt. His sister is a prolific painter, and his brother is a prolific hairdresser. It’s nice to see that, because Gabi was a prolific hairdresser and painter too. So they both have his sparkle in them. I know his father has a serious work-ethic and I think, in the long run, it helped Gabi with the Charlie Megira project. In my film, when he’s talking about discipline in rock’n’roll and art, I think it actually comes from his father’s work-ethic. So it’s nice to see that. I don’t know much about his mom, only that she was more French-oriented Moroccan Jew than his father. Very delicate, like she was torn out of Casablanca, both the city and the movie. Gabi hated gossip, it made his stomach ache, and somehow I get the feeling he got this wonderful trait from his mother.

How does the family background make itself felt socio-politically?

Back then, most of the Moroccan Jews were considered deprived. The mainstream were the labor party supporters, Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe. I’m Ashkenazi, but from a different background – my grandfathers were revisionists. So back in the 1950’s and the 1960’s, and also the 1970’s, there was sort of a »deprived alliance« between the Mizrahi Jews like Gabi’s family and the Ashkenazi Jews who weren’t labor party supporters, like my family. So my parents and Gabi’s parents supported the same political parties. By the way, the man mourning at Gabi’s grave near the end of my film is Israel’s ex-minister of foreign affairs and deputy prime minister, David Levy, who knows Gabi’s parents from back in Beit She’an. He was a very famous »politician for the deprived« in the Likud party, which is sort of the opposite of the labor party. Nowadays, it’s actually the same thing, but that’s another story. (laughs)

It feels like your part as the director and cameraman is a very important one. What does it mean to you, releasing this work?

True, it means the whole world to me, from so many angles. The thing is, when we played together, rehearsing, I think I had some issues with stage-fright, and Gabi was really pushing forward. He was very ready for the stage, and I was ready too, but for the backstage.

Hahaha.

To tell you the truth, it also came from a humble place. I was sort of feeling that the technical gap between us is huge. So I was like: »Let him do his own magical thing at his own pace.« Years later, on the sleeve he designed for the album »The End of Teenage«, he wrote: »The voice of the untrained will be heard commercially.« It was his favorite thing, you know, to work with untrained musicians, and to see them grow beside him. But I felt like I felt, so The Lost Boys was over. The nice thing is that now I feel that I’ve fulfilled that sentence of his, in the sense that the film about him was heard commercially and was made by someone for whom it was his first film actually. Also, like I said earlier here, I was looking for something really meaningful, a musical creation that will stay forever. So after Gabi passed away, I felt like I was on a mission to complete the film. My goal was to make something that would be a bit fragmental as a perfect homage to the eccentric fab artist he was. That means that I didn’t have a certain musical documentary that was a model to be influenced by. It is, and I’m saying it as humbly as I can, a special one-of-a-kind rock’n’roll movie. His tragically sad passing even pushed me to record some musical stuff for the film, after a ten-year hiatus. So, I think it’s a fitting homage to the Charlie Megira spirit. It’s totally indie and DIY and has its own special pace and rhythm.

Megira said: »Israeli rock is staged too much, almost recruited.« What do you think that means? How does his character relate to this?

Yeah, Charlie didn’t have a problem with Israeli pop. On the contrary – he could dig some ideas from Israeli pop. Nevertheless, he was somewhat critical about Israeli rock, because rock is all about originality and not about doing a carbon copy. So how does his character relate to this? I think that like nowadays, when Megira started it was already a time when you could find tens of thousands of neo-rock’n’rollers around the world. In Israel, you had a fast-growing scene of indie-rockers etc. but when you’re talking about Charlie… here’s a guy who on the outside made something familiar – well, very haute-couture rock’n’roll outfit but familiar – and yet, sound-wise, this guy made some one-of-a-kind combinations like no-one else did. He sang in Hebrew when everybody in the indie scene was singing in English, and he had some very surprising concepts. So in a way, he was really the epiphany and the essence of the whole thing that’s called rock’n’roll. You can say that Charlie Megira revisioned the originality in rock’n’roll. He just wasn’t like everybody else who deals with Elvis or rockabilly aesthetics, you know? And more than that – he was like an x-ray of knowing who’s for real and who isn’t in the indie and DIY scene. That’s why sometimes he liked singers or bands you wouldn’t expect him to like. Brilliant.

Can you name a few artists – besides the ones mentioned in the movie?

Well, for example, he could talk about the guitar work of Richie Sambora from Bon Jovi, and then mention guitarists like Chris Spedding and Scotty Moore. He really liked the sound of Julio Iglesias. When you think about it, it’s in the »sound family« of one of his deepest influences, the duo Suicide. He also liked Israeli pop divas like Ilana Avital, and then, of course, he talked endlessly about Syd Barrett and Lou Reed. Very, very versatile and eclectic. Very smart. He didn’t let radio DJs or culture agents brainwash his uniqueness.

One gets the impression of Megira being kind of rootless and maybe lost. Does this feeling have a basis?

Of course! That’s exactly what he was looking for – to be a sort of a universal cosmopolitical character. I’ll give you an example: Why do you think that the character of Charlie Chaplin’s »The Tramp« was so extremely popular, to this day actually? I think the answer is that you never heard him speak, so anybody around the world could dress his own language on the tramp. So, the tramp spoke no language and every language at the same time, and Charlie was often mentioning the tramp character when we spoke about music. And that’s why when you listen to Charlie Megira, the vocals are obscure – so anyone can dress his own language on Megira’s songs. I think it’s also a universal thing – anyone who feels disadvantaged or deprived by something or by someone, can relate to Charlie Megira. So in a way, basically everyone who’s got morals and high-consciousness can relate to Charlie. Maybe it’s not the majority, but it’s still a lot of people. This means that the Charlie Megira figure or character, you name it, should have been bigger than the Beatles! Haha. Well, almost.

What did Berlin mean to him?

My film is not pretentious, I mean, I’m not pretending to know what I don’t know. I’m sticking to what I know, and although I did a very deep research, I chose to focus on the »Charlie Megira idea«. In other words, the film brings you a sort of »Charlie Megira experience«. After the premiere, a good friend of Charlie approached me and said: »It was very natural. The film is like a meeting with Gabi.« I really liked that comment, and I think it’s true. He was such a rare bird – musically, artistically and personally – so that was enough to focus on, you know? How he talked, smiled, laughed, thought etc. And all that through his amazing music being carefully picked and mixed-in, with some never-before-heard rare Charlie Megira songs as well.

The film shows Charlie in all his complexity and does not even try to explain the ending.

In the film, I deliberately don’t try to solve the seeming mystery of his death. You have to understand that I didn’t try to surround everything, because you can do it maybe just in an encyclopedia, and even then – there will always be something out of the frame. It’s like going a bit more abstract in order to be more precise. That’s what I did in my documentary, and I think it’s a humble approach. I can only assume that for him, Berlin meant a springboard to the USA, because I know for sure that his big dream was to make it in the USA, living there and recording there.

How is the reaction to your documentary in Israel?

»Tomorrow’s Gone« got a very warm reception here. First of all, the world premiere in 2019 was in an A-list festival – the famous Docaviv Film Festival in its 21st year. It premiered at the TEDER club in Tel-Aviv to a very large crowd of about 1,000 spectators and played in cinematheques around Israel. Then, in October 2019, the film premiered in Israeli cable TV (HOT8 docu-channel) and got some rave reviews in the papers and all over the internet and local TV. I got a photo album on my Facebook page with hundreds of recommendations for the film. The Corona lockdowns canceled a lot of screenings, but nowadays me and the producer of the film, Eyal Datz, are bringing back the physical screenings. This is fun, because there’s nothing like being with the crowd, with the people, you know.

And what about outside Israel?

Outside Israel, it also participated in the very prestigious 60th Krakow Film Festival (KFF) in Poland. It won some prizes, like Best Feature Movie at the Sonic Scene Music Film Festival in Italy. To this day, »Tomorrow’s Gone« has been translated into Polish, Italian, French, Hungarian, and of course, English. Also, the film had some special one-off screenings, like at Brain Dead Studios in Los Angeles, or in indie locations at Berlin and Budapest. That was very cool. Nowadays, »Tomorrow’s Gone« is streamed online at Vimeo on-demand. It’s amazing, because people are watching it from all around the world – even from countries like Peru, India, and Nigeria. I’m pretty sure Charlie and Gabi are smiling above us now. 🙂

Links:

https://tomorrowsgonemovie.wixsite.com/tomorrowsgone/the-movie

https://charliemegiranumero.bandcamp.com/