Why do we stare into the fire? There are many reasons that can be given. We love the crackling of the logs, the mesmerizing play of the flames. So here we are, already in the realm of emotions and instincts. Is the campfire anchored in our subconscious? Are our positive experiences based on what we have learned, or on what we have inherited? No doubt, making fire is an essential achievement of human beings. A Zero Point, as Benjamin Abel Meirhaeghe would call it…

But humans are not the only species that uses fire. Predators are also magically attracted to fire. Its bright glow causes prey animals to lose their cover, possibly even being injured and finding it harder to flee. But unlike us, predators can only use fire passively and cannot ignite it themselves. Even our closest relatives, the chimpanzees, do not possess this ability and, on the contrary, clearly show a fear of fire. It is the active use of fire that distinguishes us from other species. When the first flame was lit, lies in the darkness of deep history. What is known, is a find in the Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa, where 1.7 million years ago people were undoubtedly sitting around a fire that they had built themselves. What is certain, therefore, is that this magical warmth has been with us for a very long time.

Songs about war and love

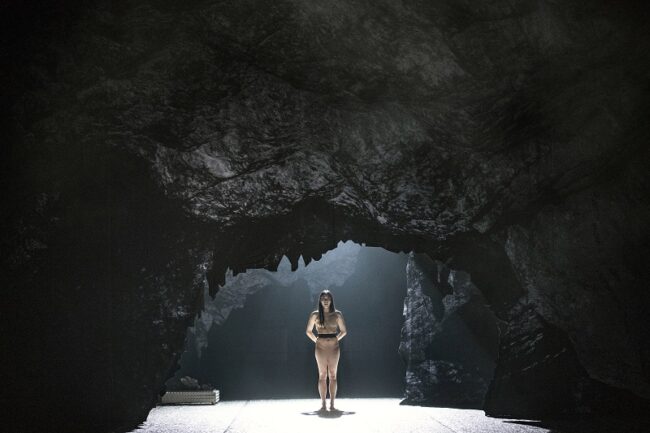

»Madrigals« by Benjamin Abel Meirhaeghe »is a musical performance that moves around the centripetal force of Zero Point. The Zero Point is primal, it is the fire around which the first humans gathered. The cosmic black hole in which time and space disappear because they have become immeasurable. It is a group of performers and the nakedness of their bodies. It is merging into each other. The moment of ecstasy when the voices of unskilled singers and skilled singers are indistinguishable. The extreme second when everything happens. When the differences are dissolved, the self-transcendence. It takes the form of a mouth opening. It is going back to the source, against the current wind. It is the inscrutability of the performers and the return to their first selves. Zero Point is the fusion of classical music and contemporary music into the heartbeat of a new world. It is the finger snap of multifaceted scenography to total emptiness on stage.«

In »Madrigals«, 8 performers and 3 musicians will perform reworked songs from Claudio Monteverdi’s »Madrigals, Book VIII: Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi (songs about war and love)« in a staged ritual, an ancient cave in which different symbols and contemporary artworks reflect our times and with their help show a future freed from normativity, a radical intimate utopia. Benjamin Abel Meirhaeghe deconstructs the foundations of Western opera and adds new contemporary layers. skug spoke with him about Zero Point, classical singing and his passion for frictions.

MAKING OF | MADRIGALS, an opera by Benjamin Abel Meirhaeghe 2022 22′ BE from Charles Dhondt on Vimeo.

skug: The music of Claudio Monteverdi is setting the mood for your music theater »Madrigals«. What is so fascinating about his compositions called »Madrigali guerrieri ed amorosi«?

Benjamin Abel Meirhaeghe: The songs about war are very warm and lovely, contrary, the songs about love are hard and harsh. I like his »Madrigals«, because these songs are also the beginning of a new genre, and his way of composing is influencing still the Western opera of today. With my piece »Madrigals« I want to go back to a Zero Point, the beginning of things.

Claudio Monteverdi’s work marks the turning point of music from the Renaissance to the Baroque. Monteverdi is considered the best-known pioneer of Western opera, setting new trends especially with »L’Orfeo«. The latter is even considered by some sources to be the first opera ever written. What new trends could you detect in contemporary opera?

I have a big problem with opera pieces put on stage today, that are so stuck in themselves, but are pretending to be contemporary. The biggest problem with me is that singers are educated in a boring way. They can sing perfectly, but their beautiful notes are not valid for me. That is the reason why I work with people that are trained and people that are untrained. There are six singers in the piece that never before sang classical music, because they are performers and dancers. And as you know, Monteverdi is quite difficult music. I communicate with them via this old music score. This theme creates already a big tension about what it means to sing classical music, to converse about art and time.

Bild 2: Benjamin Abel Meirhaeghe / Muziektheater Transparant (BE), Madrigals © Fread Debrock

You do not come from a middle-class background that might find secular vocal music like »Madrigali guerrieri ed amorosi« from Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi familiar and appealing. Your father worked in a factory, your mother was a secretary, when you grew up. When did you discover a passion for classical singing? And (how) did classism affect you developing your voice?

I remember this CD from my parents in my childhood with the best 100 classical songs. I was fascinated by theater and the fabrics coming down. For me it was a logical combination, on camp days they would put up this music with all this drama. In puberty I discovered that I have a very high voice, much higher than nowadays and via a joke I imitated a fire alarm. I wanted to learn classical music, but I refused to learn notes because I am not so mathematical. I based it on imitation and improvisation. This emotionality of mine is rooted very early in my life, some people say I have a very old soul. And so I have to play with this friction every day, feeling so melancholic and old actually. On the other hand, I am so triggered by futuristic stuff and want to be up to date.

An asteroid is named after Monteverdi, and there is for example also a Monteverdi Peninsula in Antarctica. What should be named after you?

Probably I would like to be a volcano.

You mentioned already this Zero Point, can you explain what you mean?

It is a mixture of a utopian world and older times; they are flirting with each other. Zero Point has different levels. First of all this former times, and I work with a cave staging. Then I make a jump and mix it together with baroque decoration. The other level of Zero Point is about the core interaction of the performers. Where do we start with the singing? I can be so powerful and emotionally charged, things we seemed to have lost in our daily life. And also, on another level, where is the Zero Point of our society? I find it still unbelievable that people who don’t know each other and are from very different fields meet on a stage – literally around the fire – and they are capable to sing together. That is amazing and a reminder for me that all of this is still possible.

Is this scenario a kind of »radical intimacy«?

»Radical intimacy« leans towards a beautiful term I learned from my good friend Jan Decorte: »meervoudig voelen«, in English: »multiple feeling«. Theater can open all senses, it can be a portal between past and future. I wanted to work together with performers in a soft and loving way, only tenderness.

Utopian rituals are a central theme of your music theater piece »Madrigals«. There is still a lot of transformative work to be done to address the prevailing serious structural and systemic deficits in Western society. What first important steps would you dare to take if you were an influential politician?

I like friction: the discussions between left wing people with conservatives I found interesting. How do we deal with the past? How do we have respect for traditions? How do we conserve the past? How do we take it to a brighter future? I would like to change the poisoned way we talk with each other, looking for real dialogues again. Be happy to be an artist.

As a director, performer and singer, in »Madrigals« you worked together with the audiovisual artist Jesse Kanda aka Doon (who also collaborated with Björk, FKA Twigs and Arca), as well as with the co-composer Wouter Deltour. Why did you choose to work within this constellation? Could you describe the process of overwriting baroque choral singing with electronic beats?

I first proposed to Jesse Kanda to remake all the music. He is not classically trained and so his reaction was interesting. He was fascinated and loved some parts, but he also didn’t like parts of the music. He could be very radical in that sense, and it reminded me of the fact that I already conform to this classical world. I was a bit shocked when he said that. But we kept a lot of the material he found interesting. We adapt the music also for three live musicians that are on stage, and the singer-performers. The core of the songs of Monteverdi is always there, like in a concert, so it is quite a music show.