Michel Serres

Strictly speaking, VJing has been an empty phrase from the very beginning, an auxiliary neology.(1) In clubs, bars and discotheques – but also in open spaces-, crowds had realised that »shaking it up« could be experienced more intensely with additional visual feeds. Moreover, since the mid-1990s, software applications for sound and video have gradually come to resemble each other, and can now be controlled by using the same user interface. Because club culture is DJ-driven, it was obvious to call video artists »VJs«. Yet how can this optical stimulus at a techno party develop into a style of its own when the moving images mostly act as mere supplements? Maybe the »true« VJs are the ones presenting video clips on music television. (An assumption which was used for a long time before VJing emerged into an art context and was enriched by discursive qualities.)

That is none other than what the first British radio DJs did in the 1930s. DJs began developing as professionals, aided by the gradual social legitimisation of popular culture, and in the process, not only did the turntable become an instrument, but also the DJ was (deservedly) raised to the status of musician. Turntable bands, such as Invisibl Skratch Pickles or particularly The X-Ecutioners, elevated the collagist usage of prefabricated music to an art form. Clearly, such experiments go back to the time of John Cage in the early 1960s (and even earlier). Wide-scale integration of the visual medium, however, only came about in techno clubs, and was pressed forward by bands such as Hexstatic and Coldcut in the mid-1990s, using their self-developed software »VJamm«. This application was so pioneering that it was accorded a permanent place at the Interactive Games Room of the American Museum of Moving Images.

The increasingly similar interfaces presented to us for the control of computers make the previously very different tasks of organising and transforming text, static and moving visual images and sound into experientially ever more similar processes. The new electronic technologies therefore form a seductive potential meeting point for many previously separate art practices. Such interfaces make use of identical concepts – frame, freeze, copy, paste, and loop – as controlling strategies.(2)

The Audiovisual Dispositive

This text, however, is not about tracking down synaesthetic strategies in club culture. Rather, it tries to provide, with the aid of several audiovisual manifestations, a historical and an aesthetic frame of reference for live-generated sound and image art which reaches beyond the ongoing discussions caught up in questions on technical details. This is why, owing to the prevailing difficulty in assigning the term »VJ« to a specific field of work, the term is being extended to the realm of live video art. It can be explained by one of the prerequisites of the considerations made herein, namely that VJing is considered a two-channel transfer of information, in which the channels not only complement each other synaesthetically, but also exist side by side in parity, conditioning each other. In his book The Time-Image, Gilles Deleuze proposed the hypothesis that the audiovisual image was a result of the »collapse of the sensory-motor schema« without referring to a »whole«.(3)

Yet he spoke of film. As narrative, dramaturgical and space-time constellations of film organise themselves in a way that differs from live interacting media or forms of presentation, the following aims at patching up the collapse of the sensory-motor schema by way of video bands. Even though Deleuze (p. 268) admonishes that the audiovisual image »is not a whole, it is a ‚fusion of the tear’«, one must keep in mind the different production and processing logics of the output of video bands. On the one hand, this acts as a mirror for the transformation of film-historical connotations, while on the other – given the rather undogmatic approach towards this canon – a pop-cultural evaluation takes place.

Inherently avant-garde, Granular Synthesis and Metamkine play with avant-garde material, thereby identifying the respective ruptures – clearly in the sense of Jacques Attali’s concept of noise as a musical anticipation of socio-political structures – in the popular realm. The translation of the audiovisual material into rhythm, as well as the haptic physicality of their live shows, evoke a sensory-motor confrontation which is cinematographically grounded only to a certain extent, but above all, performatively rooted. Although both formations refer to historical connections pointing towards experimental and Expanded cinema, we can observe the overcoming of cinematographic code systems that contribute to a relocation of audiovisual perception by the fixed implementation of musical practices. This type of cinema may take place in film theatres, but it is usually shown in galleries, clubs or concert halls.

While the music is made to sound »cinephile« in order to evoke a »cinema pour l’oreille«, on the image track a »kinaesthetic« approximation of the performance venue takes place, which at the same time is being stridden across acoustically. Sound and image, however, plainly serve as surficial plateaus in rhizomatic destabilisation practices, leading to a setting which makes rehearsed parameters of space and time perception crash. Stroboscopic flashes of light from the rear regions of memory flare up for split seconds as figures that change from organic to abstract, connect with others, rotate and dislocate themselves, fuse with the layers of sound, and form a cerebral data stream, the impulses of which, as if leaking from electric cables, directly penetrate those regions which turn abstract images of reality into concrete dream images; the data processing brain is put into REM phase, the body converts to a big vibrating resonance box.(4)

The mode that was thus to become exemplary during the seventies was performance – and not only that narrowly defined activity called performance art, but all those works that were constituted in a situation and for a duration by the artist or the spectator or both together. It can be said quite literally that »you had to be there«. [Video and sound installations] not only required the presence of the spectator to become activated, but were fundamentally concerned with the registration of presence as a means toward establishing meaning.(5)

My approach in this text with regard to VJing is an audiovisual dispositive which, because of the interdependence of visual and acoustic information and the resulting synaesthetic interaction, may only be applied to the model of a band or a group. This dispositive is not determined by specific media or software technologies. In this context, VJing does not equate to related algorithmic programming, but acts as a counterbalance for the expansion of performative practices which are genealogically most likely derived from performance and media art.

This way, an only seemingly paradoxical acousmatic representation may be defined in which the actual sources of reference of both channels are reciprocally present in each other, virtually off-screen (i.e. acousmatic). The respective complementation in the spectrum of reception is, however, placed in an exterior space (i.e. represented). As a consequence, the performance space becomes an integral part of the intervention where the architectonic space, by way of enormous sound systems, is being disclosed acoustically and visually by performative means (Metamkine) or through big projection screens (Granular Synthesis).

It is almost like in a 360-degree cinema where one may, and even ought to, walk about. This strategy, however, goes back to concert and film logics that demand rather undivided attention. As the viewer is being taken possession of, this surely represents one of the most virulent oppositions to club VJing.(6) Roughly put, the dispositive might be localised at a point where one no longer knows whether s/he should listen to the images or look at the music. This relates to the different perception speeds and distraction mechanisms of music and image.

German film music theoretician Norbert Schneider writes: »Watching informs us about the constitution and ‚condition‘ of the environment. Listening informs us primarily about the interior life of fellow human beings, about their thoughts and moods? Thus, listening corresponds to feeling (as an unconscious understanding of the world) whereas watching corresponds to thinking (the conscious understanding of the world).«(7) This leads to certain »off-key continuities« in perception, prevalent in film editing or musical cut-ups. Virtually all video bands produce momentous interactive art, since they, much like music bands, generate an art event in real time.

As a result, we obtain four interdependent variables which map out the dispositive:

Image – Interaction – Sound

|

Time

Be it in a performance, an installation, or a club context, the bands work in all three segments – some times more and some times less – with prefabricated settings from their own audiovisual data archive and either interact in an improvising manner (Metamkine) or according to a formulated compositional plan (Granular Synthesis).

From this, two statements may be deduced:

- Auditive and optical information is presented in parity as multi-channel manifestations.

- These manifestations take place in a live context. They exist like a concert or a temporary installation for the moment.

The exponential increase in the number of performance artists in almost every continent, the numerous new books and academic courses on the subject, and the many contemporary art museum opening their doors to live media, are clear indications that in the opening of the twenty-first century, performance art is as much as a driving force as it was when the Italian Futurists used it to capture the speed and energy of the new twentieth century. Performance art today reflects the fast-paced sensibility of the communications industry, but it is also an essential antidote to the distancing effects of technology. For it is the very presence of the performance artist in real time, of live performers »freezing time«, that gives the medium its central position.(8)

Like Granular Synthesis, Metamkine deal with a rudimentary, even archaeological understanding of cinema and music in order to arrive at the essence of the respective medium, and from there deduct an associative-physical stream of information which leaves behind the technically well-armed VJ scene via an intermedial approach (Metamkine) or an oversized hearing and viewing box (Granular Synthesis). The musical rhythm loops, which are at times perceived as pulsating, other times below the perception threshold, do not fall into the trance-like, repetitive machine beat of techno music. Metamkine and Granular Synthesis view rhythm as layers of sound, sound colouration, drones or sequencing which, apart from intensely territorialising the body, at the same time also captures the largest human hearing organ, the skin, by making use of the complete frequency spectrum. Due to these complex parameters, they rather have in mind the concept of sitting in a film theatre instead of dancing in a club. One can be quite occupied with not being occupied with these bands.

After all, both aim to amplify the habits of hearing and seeing by using a radical and fervent audiovisual attack. Both video bands work in a performance context that is commonly frowned upon as being »high culture« or »elitist«, which takes place in art galleries, museums or theatres. Such a designation rather indicates that the perception of images and sounds seems to be of a divergent nature, since the images could easily work in more »low-culture« spaces, such as clubs or other locations atypical for staging art performances, even though the music would most likely be rejected in these spaces.

In the last few years, however, much like in the areas of film, music, etc., the formerly rigid societal segments have become permeable and fluctuating, gradually coming closer to each other. This fusion of social and aesthetic positions pervades traditional designations against the backdrop of an ever increasing image and information overload.

In this respect, Metamkine and Granular Synthesis may be seen as audiovisual pioneers, since their artistic »high culture« works, via club space, have helped to blur these boundaries and have made live video art compatible for the pop context.

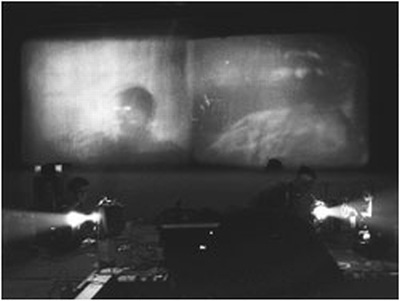

Formed Light, Concrete Sounds – Metamkine

Since 1987 the French artists Jérôme Noetinger, Christophe Auger und Xavier Quérel have been working together as Celulle d’Intervention Metamkine, located in Rives near Grenoble. Their performances have a rather haptic air about them, since they exclusively handle various Super8- and 16mm-films and vintage synthesisers. What makes them differ from other formations is simply that Auger and Quérel, by manually controlling projectors, convert them practically into visual instruments which enter into spontaneous interaction with the analogue music and by doing so, significantly determine the overall composition. These audiovisual interventions are committed to the cinephile qualities of the French Musique Concrète.

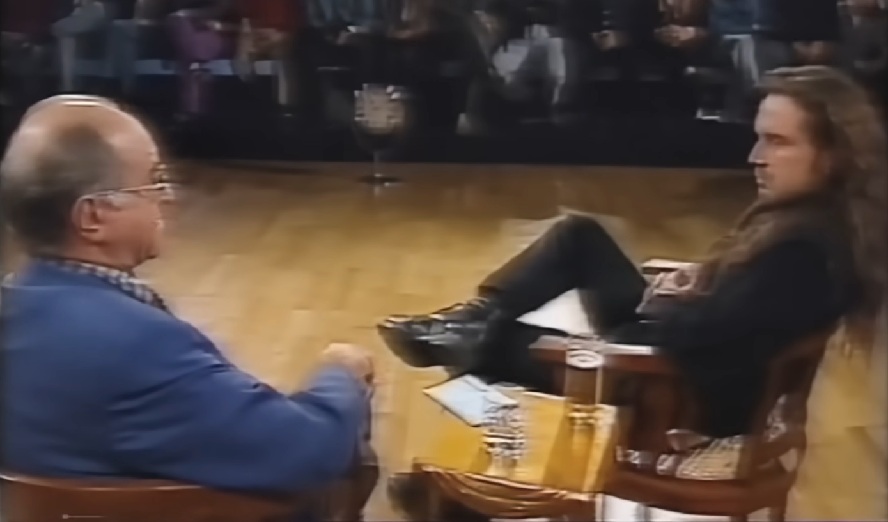

It could be argued that such practices appear regressive in the fully digitalised era. In this regard Noetinger, who also runs the Metamkine label and releases electro acoustic music, pointed out in an interview in 2004 for the magazine The Wire, »Not long ago, everybody dreamt of having a Revox! It was the Rolls Royce! Today there’s this spurious idea of ‚progress‘, this imposition of new technology by the market. There’s something totalitarian about it. It’s like asking a violinist why he doesn’t play a computer.«(9)

Operational sounds such as the clattering of projectors blend in with partially crude analogue layers of sound or sound fragments of the prefabricated magnetic tapes; at times the smell of (un)intentionally burnt filmstrips fills the air. The filmstrips, which are edited as loops, are self-produced or found footage, and through the choreographies which are evaluated in extensive rehearsals, they generate a performative image space in which the depicted transforms into a sculptural replica. Adding to this, Metamkine work with a set of mirrors, so that through extra deflections and refractions the projections are ad infinitum expanded, fragmented, bent – beyond recognition.

With the visual aspect of Musique Concrète in mind, the sense of space thus formed may be traced back to choreographies of Oskar Schlemmer in the late 1920s which he had developed for the Bauhaus school.(10) Here, artists perform relatively simple geometric figures that live off their expressive gestures. These are conceptualised into the audience and made to appear as ornamental bodies in the best manner of the silent film tradition. This directness in expanding the stage into the audience was especially pushed forward in the performance art of the 1960s(11) and has lost much of its attraction (or »aura«, as Walter Benjamin would have put it) with the successive separation between performer and performance.(12) Therefore, the latest developments are inclined towards the concept of musicians and video artists virtually backing out from the visual spectrum of the audience, and in a »retrograde« step see themselves as newly constructivist machinists, who expose the inner processing logics of the machine and transfer them into public space.(13)

With the visual aspect of Musique Concrète in mind, the sense of space thus formed may be traced back to choreographies of Oskar Schlemmer in the late 1920s which he had developed for the Bauhaus school.(10) Here, artists perform relatively simple geometric figures that live off their expressive gestures. These are conceptualised into the audience and made to appear as ornamental bodies in the best manner of the silent film tradition. This directness in expanding the stage into the audience was especially pushed forward in the performance art of the 1960s(11) and has lost much of its attraction (or »aura«, as Walter Benjamin would have put it) with the successive separation between performer and performance.(12) Therefore, the latest developments are inclined towards the concept of musicians and video artists virtually backing out from the visual spectrum of the audience, and in a »retrograde« step see themselves as newly constructivist machinists, who expose the inner processing logics of the machine and transfer them into public space.(13)

Performative Disclosure of the Audiovisual Space

By insisting on a historicity of one’s own, Metamkine join in an already quite canonised video and media art discourse, most notably exemplified by Nam June Paik. Instead of discussing Paik’s TV experiments, I herein want to point to his Music Studies and his early audiotape experiments: »Paik brought his knowledge of a more highfalutin‘ art form, namely the electronic music of Stockhausen and Cage, to bear on a brand-new media. Structurally, Paik’s videotapes derive from the audio-taped Musique Concrète sound collages he was making in Europe before Cage deflected him towards performance.«(14)

Following the audio tape sound experiments conducted prior to World War II, this medium turned out to be one of the first and most promising post-war prospects in exploring new worlds of sound. Such as with the case of French Musique Concrète by Pierre Schaeffer, later Pierre Henry or Vladimir Ussachevsky in the U.S., however, Musique Concrète itself alluded to such groundbreaking pieces as the acousmatic collage »Wochenende« (1930) by Walter Ruttmann(15), Oskar Fischinger’s early experiments and especially »Radio Dynamics« (1942) or Viking Eggeling’s spatial figures set in motion in »Diagonal Symphonie« (1921/25). Unlike many digital music video filmmakers who have geometric figures spurring across the images to the sound of abstract electronic music, Metamkine’s arsenal of images, quite directly quoting early medial development phases of interwar abstract film, had virtually always been fed by the concrete, processed and/or alienated via simple means such as pitching, splicing, colouring, fading or more or less traditional editing.

Following the audio tape sound experiments conducted prior to World War II, this medium turned out to be one of the first and most promising post-war prospects in exploring new worlds of sound. Such as with the case of French Musique Concrète by Pierre Schaeffer, later Pierre Henry or Vladimir Ussachevsky in the U.S., however, Musique Concrète itself alluded to such groundbreaking pieces as the acousmatic collage »Wochenende« (1930) by Walter Ruttmann(15), Oskar Fischinger’s early experiments and especially »Radio Dynamics« (1942) or Viking Eggeling’s spatial figures set in motion in »Diagonal Symphonie« (1921/25). Unlike many digital music video filmmakers who have geometric figures spurring across the images to the sound of abstract electronic music, Metamkine’s arsenal of images, quite directly quoting early medial development phases of interwar abstract film, had virtually always been fed by the concrete, processed and/or alienated via simple means such as pitching, splicing, colouring, fading or more or less traditional editing.

In this connection we not only deal with the replacement of central perspective in painting and cinema by physically marking out the performative space; Metamkine’s visual element may rather be seen in a framework that refers to the inner materiality of the medium. Concrete image content is purged until nothing but formed light remains which, as a projection screen, entirely occupies the performance venue.

Metamkine’s performers are most of the time clearly discernible, whereas the performers in Granular Synthesis are not visible at all. While Metamkine operate in a relatively classic performative stage setting, Granular Synthesis present a kind of audio film where only the oversized, approximately 4x3m high projection screens are visible.

Sonic Layers of Time, Optical Shattering – Granular Synthesis

All sound is an integration of grains, of elementary sonic particles, of sonic quanta.

Iannis Xenakis

Increasingly specific software applications have turned computers into interactive and intermedial interfaces par excellence. For the »black box« it no longer makes much of a difference whether the algorithm fed in generates an optical or acoustic output. Improved processor performance has made it possible to produce highly complex compo-sitional methods such as granular synthesis.

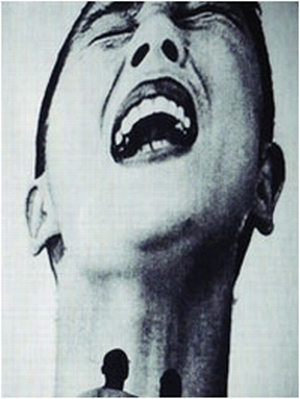

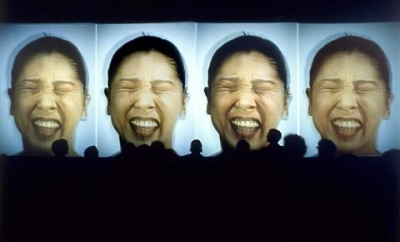

Founded in Vienna in 1991 by Kurt Hentschläger and Ulf Langheinrich, Granular Synthesis derive their name from above mentioned method. To date, the duo has carried out around 15 fully set-up installations. Compared with Metamkine’s approach, Granular Synthesis are located basically on the opposite side of the audiovisual dispositive. Granular Synthesis allow the semantic codes of the digital machine free play and generate a human-machine interface which toils on the fringes of cutting-edge computer technology. Each micro structure, each millisecond grain is aimed at making the tactile quality of the sound and the image be experienced. While Metamkine still leave open perceptive slots by way of their theatrical gestures and allow organic physicality, Granular Synthesis confront us with the full impact of machine-controlled logics. Consequently, by extreme fragmentation of the images, the performers‘ heads, filmed in glass cubes in the early works of the band, become grimaces, the contours of which remain organic, even in the moments of highest affect.

By its intensely accelerated serial split-up, the physical image’s content is distilled into some kind of pure object, completely bereft of voyeuristic sexual connotations, and lets the potentially desiring gaze go blank. Instead, these images herald the industrial degeneration of present social forms of communication, for example, when in »Model5« (1994/96) the head of performer Takeya Akemi, under the impression of speed, »gives birth to an electronic Medusa image oscillating between the poles of sensual ecstasy and agony.«(16) The recipient is caught up in the dichotomy between voyeurism and the auto-destructive projection on the protagonist, who is trapped in this glass construction as if under a cake dome; the glass resembles a transparent data helmet imposed on the performer, but also a morbid incubator.(17)

By its intensely accelerated serial split-up, the physical image’s content is distilled into some kind of pure object, completely bereft of voyeuristic sexual connotations, and lets the potentially desiring gaze go blank. Instead, these images herald the industrial degeneration of present social forms of communication, for example, when in »Model5« (1994/96) the head of performer Takeya Akemi, under the impression of speed, »gives birth to an electronic Medusa image oscillating between the poles of sensual ecstasy and agony.«(16) The recipient is caught up in the dichotomy between voyeurism and the auto-destructive projection on the protagonist, who is trapped in this glass construction as if under a cake dome; the glass resembles a transparent data helmet imposed on the performer, but also a morbid incubator.(17)

Compressed Emptiness of the Audiovisual Bodies

Granular Synthesis dealt with precisely this loss of control and correlation primarily in the phase between 1991 and 1999. In the second phase an almost complete emptying of the image space takes place in which solely monochrome surfaces and »psychedelic« flicker effects are employed.(18) In the works of Granular Synthesis the eye is successively deprived of information while ever-increasing sub-basses and cascades of rhythm, synchronised to up to 200 BPM, roll over the sound plane. An experiential space opens up, the experience of which becomes more intense the more it is cleared of signs.

The grain is a unit of sonic energy possessing any waveform, and with a typical duration of a few milliseconds, near the threshold of human hearing. It is the continuous control of these small sonic events (which are discerned as one large sonic mass) that gives granular synthesis its power and flexibility. The typical duration of a grain is somewhere between 5 and 100 milliseconds. The most musically important aspect of an individual grain is its waveform. A vast amount of processing power is required to perform granular synthesis. A simple granular »cloud« may consist of only a handful of particles, but a sophisticated »cloud« may be comprised of a thousand or more.(19)

The hyper-physicalised affirmation of the machine presented in the works of Granular Synthesis breaks down the boundaries between the humanoid and technoid body with its repetitive sequences of image and sound which, in some way, brings us closer to constructivist practices. The conscious display of the technological apparatus exhibits a human internalisation of the machine as it had already been presented for example in Detroit-Techno. Hence, the media theoretician Florian Rötzer writes, »The moving image, the image changeable in every pixel, the image that has become truly musical, is the condensation of speed.«(20)

In order to distil an intense sensual experience, it is necessary to build up an antipole of some sorts which consists of an upgraded environment and refers to the development of a software of one’s own.(21) This software, which was produced between 1997 and 1999, is called VARP9. Just like a music sampler, it enables one to subject images and above all the direct connection of audiovisual data to granular synthesis: »It is a sample based MIDI software instrument that streams from RAM. It works in real-time in full PAL video resolution and frame rate. It allows accessing and allocating single frames at 25f/sec. At this video grain rate it is capable of audiovisual granular synthesis«.(22)

The flashes of consciousness produced by Granular Synthesis extract micro-range time snippets, which no longer represent caesurae but a permanently permuting flickering, become expansions, shiftings, rumples and fractalisations. The acts of acceleration and deceleration move parallel; the microtonal interferences in between generate trance effects, amplified by their (sub)sonic intensity. Misconnections in space and time collide with elliptic retardation and acceleration strategies which join – from the perspective of Austria’s film avant-garde – the works of Peter Tscherkassky, Martin Arnold and Peter Kubelka’s »Arnulf Rainer«.

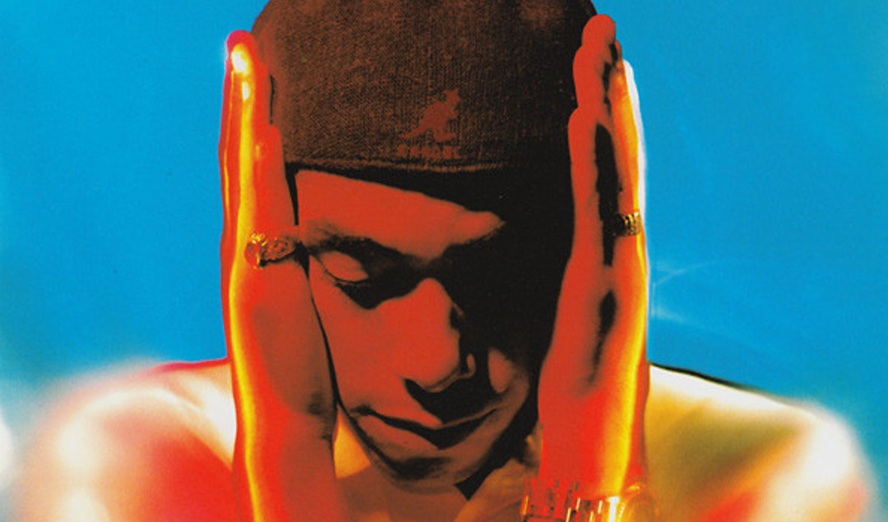

The award-winning duo (amongst others the Grandprix Artrec 1995 in Nagoya, Japan) creates an industry-induced »information overload unit« which makes no use of found footage, but instead samples itself so to speak as an »alter ego image« and flickers across the screens in countless variations with a massive sound environment on top. While the processing due to the working method is quite laborious, the starting material is mostly easy to prepare: heads in glass boxes on huge multi-screens (»POL«, »NoiseGate«, »Model3«/»Model5«), video sequences of British dance artist Michael Ashcroft (»We Want God Now«, »Form«, »Sinken«), monochrome surfaces (»Reset«), predominantly black surfaces (»Minus«) or the computer-generated transformation of a public building into a sculpture of light which evokes the illusion of a twinkling space ship (»Lichtwerk«).

Stripping it down to the basics yields the focussing on an image which has come to appear so vacant that only basic geometric patterns remain. The emptiness is stored in the highest audiovisual data decompression. While in the Model-series humans, in their gestural articulations, were important as concrete representations or images, the camera focus has gradually centred on the body itself until finally the lens reads the skin as the focal point of abstract geometric patterns and as the boundary to ways of representing humans.

Audio Visions Reloaded

By way of the two video bands Metamkine and Granular Synthesis, I intended to make the »genre« VJing discussable in a film and music historical context. Both bands, in their own ways, herald audiovisual prehistoric times, the sonic and filmic codes of which, via club culture, have grown to a mass-compatible phenomenon within the last ten years. The above outlined concept of an audiovisual dispositive is meant to contribute to getting a glimpse of the discussed bands‘ synaesthetic methods of working.

While Metamkine consciously hold on to a musical and cinematographic tradition in order to provide new discourses on perception and the gaze, Granular Synthesis work with cutting-edge technology to expose the primal and submerged layers of human perception.

As both bands use image and sound track as equal transmission matrices, this allows a concise, real-time experience which transfers live media art to a performance context where live interaction between the two media and the artists becomes the performative compositional premise.

Selected Material

GRANULAR SYNTHESIS

Index Edition, 2005. Remixes for Single Screen. [DVD]. Vienna: Index.

ZKM/Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, digital arts edition, 2004. Immersive Works. [DVD]. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz. www.hatjecantz.de

METAMKINE- CELLULE D’INTERVENTION

References

(1) The festival Netmage, founded in Bologna in 2000, may be regarded as one of the first and leading events dealing more or less exclusively with live media art in Central Europe. Already in 2005 its artistic director Andrea Lissoni considered the »genre« VJing to be outdated. In: DEISL, H., 2005. Netmage 2005. Ray – Kinomagazin, April 2005, pp. 44-46.

(2) WATERS, S., »Beyond the Acousmatic: Hybrid Tendencies in Electronic Music«. In: EMMERSON, S., ed. Music, Electronic Media and Culture. Ashgate, Aldershot, 2000, pp. 59-86.

(3) DELEUZE, G., 2001. The Time-Image. Cinema 2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 256-257. Later on in the book (p. 266) Deleuze recurs to Robert Bresson’s automatic »model« which »has no need of computing or cybernetic machines«, however »the cinematographic image was already achieving effects which were not like those of electronics, but which had autonomous anticipatory functions in the time-image as will to art.«

(4) Compare: ATTALI, J., 1985. Noise. The Political Economy of Music. Vol. 16: Theory and History of Literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

(5) That is why Kittler writes: »That which is no longer imaginable happens because there where nothing may be imagined data processing takes place«. KITTLER, F., 1989: »Die Nacht der Substanz«. In: PIAS C., et al., eds. Kursbuch Medienkultur. Die maßgeblichen Theorien von Brecht bis Baudrillard. Stuttgart: DVA, 1999, p. 507.

(6) Actually it is quite dull to watch a DJ or laptop artist work while dancing, in a situation in which immediate auratic elements seem to be blinded out. Here, the dynamic VJ images are much more fun. These may not only be »danced to« but one may also quite happily expose oneself to the continuous visual flow.

(7) SCHNEIDER, N. J., 1990. Handbuch Filmmusik. Bd. 1, Musikdramaturgie. Konstanz: UVK, p. 65.

(8) GOLDBERG, R.L., 2001. Performance Art. From Futurism to the Present. London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 225-230.

(9) WARBURTON, D., 2004. »Cinema for the Ears«. In: The Wire. Adventures in Modern Music. London, #239, p. 24.

(10) Goldberg (p. 106) mentions one of the probably earliest project descriptions of an audiovisual performance dating back to 1923 when the two Bauhaus- and Schlemmer-students Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack and Kurt Schwerdfeger staged their Reflected Light Compositions »to multiply the sources of light, adding layers of coloured glass which were projected on the back of a transparent screen, producing kinetic, abstract designs. Sometimes the players followed intricate scores which indicated the light source and sequence of colours, rheostat settings, speed and direction of ‚dissolves‘ and ‚fade-outs‘. These were ‚played‘ on a specially constructed apparatus and accompanied by Hirschfeld-Mack’s piano playing«.

(11) Such ambitions are by no means new. Here, acting as representatives, I would like to recall the theatre space designs by Erwin Piscator or early theatre works by Sergei Eisenstein such as »The Mexican« (1920) or »Gasmasks« (1923), in which the traditional situation encountered in the proscenium stage, as known from theatre and film, is being interrupted and extended by a so to speak third dimension.

(12) The DJ desk equipped with DJ or laptop consoles has gradually moved toward the »interior« of the stage. Compared to rock or pop bands, Club DJs or VJs are all but »tangible«, their production logics are separated from the performance location, which is mirrored in a techno-reactivated constructivist human-machine interface.

(13) Since the mid-90s it has become a common practice of work and aesthetics to make use of the »error of the system«; the »glitch«. This is carried out by wilfully bringing about computer crashes or other machine-inherent errors or manipulations (interpolations, distortions, foreign data material). Comp. e. g.: YOUNG, R.: »Worship the glitch. Digital music, electronic disturbance«. In: THE WIRE/YOUNG, R., eds., ²2003. Undercurrents. The hidden wiring of modern music. London/ NY: Continuum, p. 45-58. As regards Austria, mention should be made of video bands such as Skot, reMI or epy.

(14) HOBERMAN, J., »Paik’s Peak«. In: HOBERMAN, J., 1991. Vulgar Modernism. Writings on movies and other media. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, p. 138. Originally published in: The Village Voice, May 25, 1982.

(15) Guy Mark Hinant writes in the liner notes of the CD-compilation »a-chronology: An Anthology of Noise & Electronic Music«. [DCD]. Brussels: SubRosa, 2003: »’Wochenende‘ is unique of its kind. Twenty years later this editing technique will be improved, to form the basis of the concrete music – even Pierre Schaeffer quickly abandoned what he called anecdotal sound for more concrete research. This work can be regarded as the first image-less film«. The piece was republished by the label Metamkine in 1994, based on the original tapes which Ruttmann’s daughter had handed over to Metamkine. In 2006, the Center for Visual Music in Los Angeles released the DVD-Compilation Ten Films with audiovisual studies by Oskar Fischinger between 1921 and 1947; www.centerforvisualmusic.org.

(16) RICHARD, B., »Bath in the Resonance Chamber, and Blinding«. In: ZKM/ZENTRUM FÛR KUNST UND MEDIENTECHNOLOGIE KARLSRUHE, ed., 2004. Granular Synthesis: Immersive Works. [DVD-booklet]. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, digital arts edition, p. 19.

(17) On the affection-image and the thereto attributable head Deleuze writes, »The close-up does not tear away its object from a set of which it would form part, ?? but on the contrary it abstracts it from all spatio-temporal co-ordinates, that is to say it raises it to the state of Entity. If it is true that the cinematic image is always deterritorialised, there is therefore a very special deterri-torialisation which is specific to the affection-image«. DELEUZE, G., 1997. The Movement-Image. Cinema 1. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 96 et seq.

(18) The flicker effect and its »consciousness-expanding« influence comes in numerous forms. It is quite popular in clubs where the flickering light/dark situations recall Early Cinema. In the early 1960s, French artist Brian Gysin, together with Ian Summerville, went about constructing the so-called Dreammachine: » … we started in a whole series of Dreammachines: from a very simply cylinder with a just regularly spaced slots producing therefore just one fixed rate of flicker, to these years later, the present machines with along the height of the column as you move your eye, your closed eyes up and down, you experience all the light interruptions between 8 and 13 seconds. External resonators, such as flicker, tune in with our internal rhythms and lead to their extension. […] Elaborate geometric constructions of incredible intricacy build up from bright mosaic into living fireballs like the mandalas in their act of growth«. SUMMERVILLE, I., 1962. »Flicker. Olympia Magazine 2«. Reprinted in: WILSON T./GYSIN B., ²2000. Here to go. Los Angeles: Creation, pp. 210 et seq. The works »Reset« (2001) by Granular Synthesis and »RGB« (2005) by Bas van Koolwijk/Christian Toonk expand these configurations by using primary colour schemes.

(19) Eric Kuehnel’s Writing Pages. 2003. Available from: http://music.calarts.edu/~eric/gs.html, [cited 23 March 2006].

(20) RÛTZER, F., 1989. »Technoimaginäres – Endes des Imaginären«. In: Kunstforum International, #98, Ruppichteroth: Kunstforum Verlag, 1989, p. 55.

(21) Writing one’s own software is virtually part of the etiquette of every well-versed video band. Here I again wish to refer to Hexstatic/Coldcut. Their software programme VJamm enables them to sample concrete images having certain inherent sounds, and they deduce these into a set of repetitive beats with loops, which leads to the development of a techno track in the widest sense. In 1997 their video »Timber« set new standards for club VJing. In 1998 the video won French Television’s MCM Best Video Editing Award. All in all it was remixed four times, entering the Guinness Book of Records as the single with the most video remixes.

(22) Description of VARP9 on the band’s homepage.

Thank you to Gülcin Körpe for translation support.