ABSTRACT

Noise can be considered not only as a disturbing distortion but also as the maximum compression of information within a certain framework of space and time.

The question of how to »audio-picture« modern lifes necessities of an industrialized environment seems to be a highly relevant topic for artistic articulations in the last hundred years. Since the Industrial Revolution these articulations had not been »up to date« until Noise emerged and made reproduction as its paradigmatic core (Walter Benjamin) understandable for an audiovisual context.

Due to its repetition ad infinitum Noise constantly produces its own hermetical simulacrum and generates an overload information unit. As a (post-)modern phenomenon, Noise has become one of the most referred interdisciplinary discourses in many branches of Art and everyday life. Noise rejects the traditional influences of the spectacle, occupies the body via a set of techno-mediated waves as a field of battle/discourse, establishes sonic warfare against mediocre pop-practices, institutionalises its subjective politics and appears as an extremely lo-fi articulation. »Noise is with us all the time and it symbolizes a world that is forever expanding and accelerating. […] Noise foreshadows and foretells. It alters.« (Robert Worby).

Since the beginning of 20.th century Noise has been integrated in music not so much to refer to subversive alternatives of music-making but to come to a result that is closer to what was considered »reality« (Dziga Vertov). The brutal truth of the demands of modern automated life evokes an amalgamation between man and machine and after Lettrisme Noise became their means of Cyborgian communication. It seems emblematic that Noise in its dichotonomy of »loudness« and »silence« has been connected with radical expressions of human life and has provoked deviant aesthetics as Noise is able to produce semiotic disturbances (Umberto Eco) through Cut Ups (William S. Burroughs) of the media. The Viennese Actionism (Günter Brus, Hermann Nitsch, Rudolf Schwarzkogler, …) in the late 1960s can be named as one of the paradigmatic interdisciplinary artistic articulations. Considering the fact that most of the musicians working in this field refer to it as an inspiration for their works, it seems essential to introduce Actionism as well as the profound changes in live electronic music that occurred in recent times especially in Vienna: Labels like mego, Laton or Durian have gained international recognition by introducing a vast contribution to the scenes of experimental music. In literature, we can refer to the two more Paranoia-driven, yet paradigmatic titles »White Noise« (Don DeLillo; 1984) and »Crying of Lot 49« (Thomas Pynchon; 1966).

Noise makes nature audible, »significant noises« (Douglas Kahn) make us understand the difference between the abstract and the empirical. But Noise also is an expression of compressed particles, is the »alter ego« of silence, both of them states of the mind of Zen.

TEXT

It is necessary to imagine radically new theoretical forms, in order to speak of new realities. Music, the organisation of noise, is one such form. It reflects the manufacture of society; it constitutes the audible waveband of the vibrations and signs that make up society.[i]

In this text I want to propose a framework for how to cope with »Noise« as it seems to me to be one of the most frequently cited, yet neglected phenomena not only in contemporary music, but also in literature, film and other disciplines of popular culture. To do so, I want to use a more »interdisciplinary« discourse in which film plays an integral role. Inasmuch as I think that in the filmic example I refer to in this text — Dziga Vertov’s first sound-film »Enthuziazm« from 1930 — some of the crucial points of scientific interest and research about the topic have been exemplified in a very concentrated manner.

Let me briefly introduce a historical framework: In 1975 Lou Reed released his groundbreaking record »Metal Machine Music«, only five years later SPK issued »Information Overload Unit« and another five years later Jacques Attalisbook »Noise« was published in English. It seems the right moment to refer to these sources as in 2006 people in England will celebrate the 30.th anniversary of the formation of Throbbing Gristle (TG) whereas we Austrians we will be deluged by what has been called officially the »Wolfgang — and as I call it — »Rock me Amadeus« Mozart«-year.

The last years saw many publications about Industrial music, Simon Ford’s book on TG amongst others. The status of such research in the German or even Austrian context is still very poor. I want to use Industrial music as a starting point for some ideas concerning Noise-music, meaning music that more or less deals only with noise. Having in mind what was pointed out by Alexei Monroe in his text »The Evolution of Senso-Brutalism: Electronic Aesthetics of Force in Music: Industrial — Minimal Techno — Gabba«[ii], I want to refer to topics like »power«, »control« and »reproduction«:

Early Industrial music owed much to the »Do it yourself«-approach of Punk and Fluxus, contributed profoundly to the liberation of Arts in general and produced a fluent (re-)context. The fascination with machines — vividly present in the first thirty years of the 20.th century — rendered the field of discourses known later as the »Man-Machine-Interface« and most significantly highlighted by the reference-line of the film »Metropolis« (1926; Fritz Lang) — Kraftwerk — Detroit Techno.[iii]

The mechanisation of musical production caused a big loss of the auratic moment of the art work — bearing Walter Benjamin in mind — but the possibility of reproduction through mechanized means would extinguish the Bourgeoisian idea of the artist as genius, it meant a democratisation of facilities, knowledge and acquirement. It seems emblematic that Noise in its dichotonomy of »loudness« and »silence« has been connected with radical expressions of human life and has provoked deviant aesthetics as Noise is able to produce semiotic disturbances through Cut Ups of the media. The Viennese Actionism of the mid-60s can be named as one of the paradigmatic interdisciplinary artistic articulations as it would put the body in question on a very rudimentary yet personal and even intimate level, provoking assaults on the texture of the individual and through this on the social core. In fact, most of the Noise-musicians refer to it as one of their inspirations for their works.

Let us make a short historical break and return to the Italian and Russian movements of Futurism and Constructivism. Mark Sinker writes:

Futuristic music was to be a sensual exploration of Noise as a continuum of detail, structured by contrast and juxtaposition.[iv]

It can be considered as one of the crucial innovations of the movements of Futurism and Dada that music could appear only as organized auditory phenomena by broadening the sound-spectrum with »non-musical« elements like the noises of the streets, of cars, airplanes and other acoustic manifestations, intending to produce an »audio-picture« or »audio-snapshot« of the surrounding social Noise; or that what Vertov termed the »Lebensfakten« (»life-facts«) in his famous »Kino-Glaz«-theories, which later culminated in the »Radio

Glaz« about audiovisual theorems. The acoustic junk of social processes seemed more appropriate for a contemporary way of music-composition.

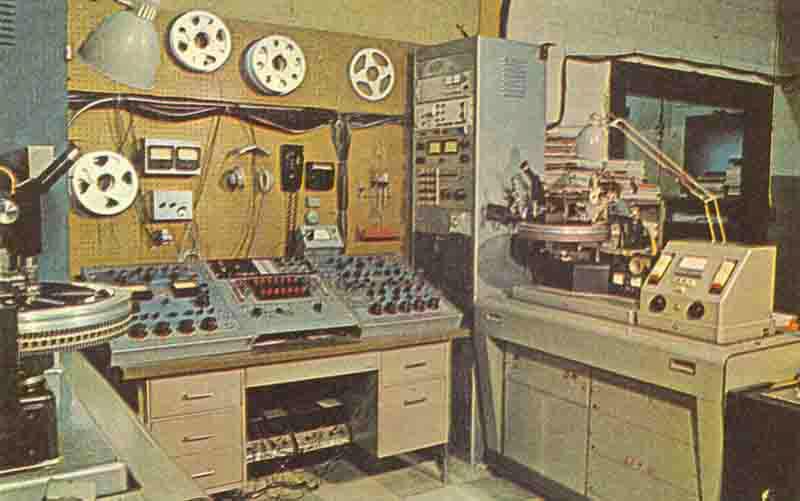

The striking difference to the works of Edgard Varese or Eric Satie et al. can be identified in the fact that most of these musicians were trained but autodidactic artists, or to use a current term, they foreshadowed the »bedroom producers« of the 90s, particulary the output of Aphex Twin etc. The Industrial-musicians of the 70s performed these acoustic »industrial necessities« in order to achieve a »sound of now«, reflecting the social grievances and conservative bureaucracies in societies marked by strong social and hierarchical decline for example in GB, USA and Japan.

But, and this leads to the first question:

If everything can be music or at least can be identified as such, how is it possible to make »anti-« or even »non«-music?

This is of certain relevance as music a priori is constituted by a system of references, interdependencies or developments, meaning an imaginative, symbolic or imposed system of power. For this, Industrial-musicians would break with more or less every musical tradition, mainly understood as an appropriation of self-definition of music and of self-empowerment. But was this wish for a »deus ex machina« not also true for figures of the »Viennese school« like Schönberg, Webern or Krenek, or even of Russolo or Pratella?

This line of reference can be traced back to John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and numerous others, and is now most strongly prestent in the work of notorious Noise-artists like Merzbow, Incapacitants or Masonna from Japan, The Haters from Canada, Macronympha from USA, The New Blockaders, Consumer Electronics or Russell Haswell from Great Britain. Sooner of later these »wreckers of civilisation« — to borrow this term associated with Throbbing Gristle — became part of a canon. From a journalistic point of view this development can be considered as a possibility to give a name — or, to use this »dirty word« — genre to these artistic expressions and be able to trace a field of references. Which in a way is highly problematic because many Noise-artists try to reject exactly these implications of references and interdependencies.

In the last hundred years numerous artistic articulations dealt with the phenomenon of how to »audio-picture« modern life’s necessities of an industrialized environment. Since the Industrial Revolution these articulations had not been »up to date« until Noise came in and revealed reproduction as its audible paradigmatic core. The rejection of control, introduced by a vast body of referential implications, lead in combination with a radically altered understanding of what could be music to new forms of the musical text.

It should be mentioned that for many Industrial-bands it seemed necessary to transfer the musical state of the art to the industrial period as a critique on the contemporary music which in their opinion was still stuck in the period of the Blues. Means: To accumulate the experiences of the cotton-fields and the working-chain and transform them to the de-humanizing labour-conditions of mass-production in the wake of an ever accelerating, monopolizing and globalizing market-situation. But whereas Industrial-musicians usually claimed to refer to a certain political, social and economic reality, to one that kills individuals‘ potential and restricts their creativities, Noise-music appears as an artificial, yet »artistic« articulation or reflection about reality.

»Noise is with us all the time and it symbolizes a world that is forever expanding and accelerating. […] Noise foreshadows and foretells. It alters«, writes English radio-artist Robert Worby in 2002[v]. Because of its repetition ad infinitum Noise constantly produces its own hermetical simulacrum — through the rejection of »traditional western values« like rhythm, melody and cadence — and generates because of the compactness of its time and space an overload information unit.

So the leading but maybe misguiding question has to be more diffuse and more specific at the same time and is as old as music itself:

What is Noise?

This brings me to my hypothesis:

Noise can be considered as the maximum compression of information within a certain framework of space and time.

Why music can be Noise and why Noise is music: Noise is not only a sonic disturbance but it is — as Attali would call it — a »rapture« within the socio-economic structures of societies that through the rejection of canonized or traditional values let us capture the audio-signals of the future. Noise music isn’t necessarily »loud«: But it makes a lot more fun to use the whole body as a target-field for sonic assaults. Noise appropriates the sounds of capitalistic processes, is their epiphenomenon. Noise transcends the Vertov’ian »Life-facts« to what I want to call »industrial necessities«: By this I mean contemporary possibilities of music-production that follow the previously-mentioned demands of broadening the reception of music by introducing »non«-musical codes.

Let us remember some demands postulated in the Futuristic manifestos: If one wants to produce a contemporary sound-work, the context of used material, of competition is not any longer that of sounds and noises of factories, cars or chaos-theory — which were issues relevant in the original period of Industrial music — but of the noises of urban traffic, of earthquake-simulators, tanks, transatlantic airplanes or sound-weapons and cyber-organics. As one of its crucial propositions (which can be traced back to Futurism on a fairly direct line), Industrial- and Noise-music altered us to the fact that the roots of every technological or physical development in the 20.th century have their roots in military innovations. [vi]

Being able to grasp the surrounding sound-environments with a small box of usually prototypical adjustments, the musician becomes a machinist who controls the entities of her/his sound-unit that is designed to unleash its most powerful moments in a live-situation. To be at the mercy of an un-reproducible live-event together with prototypical machines transfers the settings of control outside of the artist on stage. This conscious loss of control was/is practised as a response to the feelings of social repression within a society that is driven by the invisible forces of control, so brilliantly recapitulated and analysed in Foucault’s »Surveillance and Punishment« (1976). That’s why many Noise-artists offer a vast catalogue of live-recordings. Furthermore: Most of the live-concerts of Japanese Noise-bands carry a high grade of ritualistic power, meanwhile the live-practices reject even the implications of the (quoting Attali again) »spectacle« because of its affirmation of the atavistic, the primitive, the most direct possible means. Finally, autonomous label structures and release-policies guaranteed an independent incarnation of an output that would disprove many aspects of theories of Adorno’s »culture-industry«-theory.

This previously mentioned hypothesis of Noise seems a very tempting one as it brings together different disciplines of study. Its implications could be:

1) In the information-communication-model that was first developed by Claude Shannon in 1949 and which amongst the more techno-orientated communication-theories has proven to be one of the most stable in this discipline, Noise is the part of the information that doesn’t contain a concrete content and therefore is diffuse and redundant.

2) If we stay with this definition, Noise can be described with the definition of the interval by Gilles Deleuze that he most notably applied to the works of Dziga Vertov. This would affect deeply our understanding of po

pcultural applications as Deleuze was quoted quite often as a reference for minimalistic/experimental dance and electronic music in the late nineties: It is not necessarily the »beat« that defines genres like Drum’n’Bass, Gabba, 2Step or Trance but it is the time in between the beats and what in Dub-music not by chance is called »space«. Through a reverse thought the interval turns out to be exactly the place of Noise because it is here where all the information is gathered of what comes next, it leaks to the future, to the next note or the next break. [vii]

In times where we are overwhelmed by all kinds of music, isn’t it a great idea just to shut up for a moment? On their first record »Birthdeath Experience« (1980) the English band Whitehouse produced a track where literally nothing is heard: a 5-minute-track of total silence. Even if the liner-notes read: »A piece as maybe Stockhausen would have finished a record«, one might be tempted to think of John Cage’s piece »4’33“«. This is nothing other than what Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek — by referring to Lacan — calls »creation out of nothing«. The interval in this sense is this place where so to say »nothing happens«.

Through this it becomes clear how Noise and Silence determine each other: Silence is an absence of Noise and vice versa. Noise in this context is meant to be a (socio-political, economic, semiotic) tool for loudening up silence by boredom. This music, which is noisy and sometimes deliberately boring, silences social silences and changes them to tremendously ear-piercing leftovers of contemporary industrial processes: »Welcome to the desert of the Real.«[viii]

These previously mentioned working-tools such as »industrial necessities« and »life-facts« fuse into one fundamental idea or acquirement of modern society: repetition. Attali caused a lasting effect by liberating music from its corny perception of being so to say merely a tool for distraction but one of socio-political prophesies. He dealt with the idea of repetition as a synonym for modern industrialized commodities so profoundly and user-friendly that also Tricia Rose quoted Attali quite extensively in her superb study about Rap-music »Black Noise« (1994). She argues that in contemporary music repetition is necessary to offer a certain feeling of social security in our highly confused times. Technical innovations and a radically transformed understanding of what makes »sense« in terms of music provided a techno-induced framework that circulates around a space in which »nothing happens«. I would like to interpret repetition without its often cited pessimistic associations but more as a possibility for stimulation.[ix]

It does not come as a surprise that via a set of techno-mediated waves Noise occupies the body as a battlefield or discourse and thereby establishes sonic warfare against mediocre pop-practices. The topic of the territorialization of the body leads to one of the main influences of Noise, Industrial and some other »Senso-Brutalist«-musics in terms of their impulsive physics: The politics of the body as demonstrated in Viennese Actionism and exemplified by manifestations by Hermann Nitsch, Otto Muehl, Günter Brus or the most notorious Actionist Rudolf Schwarzkogler. The putting the body into question by the Actionists represented a significant rejection and body-mediated assault on the fascistic heritage in Austria in which the body was seen as »Volkskörper« (»body of the people«) in which there was no space for individual (artistic) articulations. The so-called »Materialaktionen« by the Actionists seemed an easy way to break the taboo of physicality and collectiveness as one of the first radical Art-movements after World War II. The Australian Industrial-group SPK in their track »Germanik« (1979) hit the spot: »Die Unschuld ist keine Verteidigung« — »Innocence is not an excuse«.

Punk used these body-politics in a diluted manner and these two, Actionism and Punk, were absorbed by Industrial music, highlighting the concepts of the »Materialaktionen« as a loss of control and power over the own body. It would be much too easy to trace back these implications to »deviant« or violent sex-practices like bondage, currently especially present in Japanese Noise. But the nucleus is the same: Total body-control for the sake of a maceration of collective socio-political suppressions. We have to think of Industrial in its early manifestations as a genre that appropriated »the industry« as a synonym of the conservative regimes of the times (Thatcherism, Reagenomics) and dealt on a symbolic, narrative and semiotic level with Fascism and National-Socialism as a synonym for inhuman, mass-produced plans for killing, for surveillance, for suppression. These artists successfully overcame the dictate of silence of that era.

Most of the bands who did/do nothing besides »pure noise«, like New Blockaders, The Haters, Consumer Electronics, Sutcliffe Jugend, Ramleh and whatever their names are, have not rejected aesthetic or even historical references to Fascism, on the contrary. It is one of their driving forces. This is mainly true of musicians from Europe where this dark chapter of history in the collective memory remains present until today — just think of TG’s logo of the Auschwitz crematorium or the LP »Buchenwald« (1981) by Whitehouse. It seems that for Japanese or American Noise-artists this historical connection appears less relevant, bearing in mind artists like Merzbow, Masonna or The Incapacitants and Con Demek, Emil Beaulieu or the early work of Controlled Bleeding.

Jumping back and forth in history: We can say that most of the arguments I have tried to define so far draw their parameters from an »analogue age«. The digital version is still to come and it is necessary to identify its paradigmatic changes in terms of how to move on from the Industrial Revolution to the Revolution of Information; to the rhizomatic, de-centralized networks of information, of gathering, storing and sorting out of information, of individual and collective memories in the »digital age«.

The task is: To find a proper music for the Information Revolution of the Internet. [x]

It would be exaggerated to assume that the digital Revolution has rendered Noise redundant. Nevertheless, there are not many who have shown a convincing body of work about new political and economic standpoints in our neo-liberal society, one in which information is available 24 hours a day and in which music is present as never before. The nihilistic chaos and paranoia now nestles in the big institutions — in the »empires«, as Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt would call them — and they have become highly complex and accepted tools for silencing societies.

Allucquère Rosanne Stone, professor at the MIT, writes:

I am interested in cyberspace because the kinds of interactions we can observe within the spaces of prosthetic communication are for me emblematic of the current state of complex interaction between humans and machines. […] The identities that emerge from these interactions — fragmented, complex, diffracted through the lenses of technology, culture, and new technocultural formations — seem to me more visible as the critters we ourselves are in process of becoming, here at the close of the mechanical age.[xi]

And music critic David Toop adds:

Sound needs its own silence. Silence is not something that can be turned on and off like water from a tap or light in a room, but this is also true for so

cial life. Interactions with people are not commodities to be accepted or rejected without communal agreement and negotiation.[xii]

Deviant practices seem stripped down to some collateral damage, applauded by the masses and the idea of the body as a battlefield and all its tactics of control/de-control have shifted form an individual to a collective reception.

Still, there are only few serious debates about:

x) how to handle these »Lebensfakten« in a post-9/11-scenario,

x) how to place a discourse about Noise if the sound-tools and their aesthetics are available in every supermarket around the corner.

Noise, the »sound of nothingness«, has become omnipresent.

Noise makes audible the fragile orders of chaos, but what to do in a social framework that seems to be obsessed by the paradoxical symptom of total freedom that just looks like the reverse side of the coin called control? Noise music offers a good example with which to overcome repression but how does it work in a »fit for fun«-society? Let’s see and listen…

[i] Jacques Attali: Noise. The Political Economy of Music. Theory and History of Literature, Vol. 16, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis/London, 1985/2002: 4.

[ii] Conference text Alexei Monroe, see: www.sussex.ac.uk/music/documents/programme.pdf

[iii] Here it is important to mention the influence of Sci-Fi-writers like Alvin Toeffler and his book »The Second Wave« (1984) and films like »Bladerunner« (Ridley Scott; 1982) for a better understanding of an updated version of this »Man-Machine-Interface«, presented by bands like Model 500 or Cybotron.

[iv] Mark Sinker: »Destroy all music. The Futurists: Art of Noises«. In: The Wire/Rob Young (ed.s): Undercurrents. The Hidden Wiring of Modern Music. Continuum, London, ²2003: 186.

[v] Robert Worby: »Cacophony«. In: Simon Emmerson [ed.]: Music, Electronic Media and Culture. Ashgate, Aldershot, 2002: 139.

[vi] In 2005 the British army released some of its prototypes of sound-guns for official use in public places as a substitute for water-cannons and teargas. These weapons are used for to keep control in dangerous situations like riots, demonstrations etc. Actually, one of the first who dealt with sound-guns in an artistic setting was the Sabotage-like band The KLF in the mid-nineties. Another example of acoustic high-end-technology can be observed around the runways of airports, where massive amplifiers produce some kind of anti-waves to eliminate the noises of the planes. Isn’t that »functional« music at its peak? This approach based on a symbiosis of high-end-technology and sound-art can be identified most clearly in some works by the Austrian label Laton and especially in the installations by F. Pomassl.

[vii] Deleuze outlines the organization of incommensurable pictures in the Vertov’ian interval-theory as one of his big innovations. The space in between these two pictures merges to an arrangement of new values of understanding. See: Gilles Deleuze: Das Bewegungs-Bild. Kino 1. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt/M., dt. ²1998: 116f.

[viii] I borrow this useful phrase from Žižek’s book of the same title (Verso, London/New York, 2002). Originally this phrase derives from the film »Matrix« (1999).

[ix] Kodwo Eshun in More Brilliant Than the Sun. Adventures in Sonic Fiction (Quartet, London, 1998) wrote about the hyper-bodyfication as a follow-up-project of the de-humanized assaults in early industrial, using the vocoder as a metaphor for the militarization of the voice. And in fact, when listening to »Scorpio« (1984) by Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five, the beat occupies via the hyper-naturalized voice the body: Noise had never before been made so danceable.

[x] Many assume that Clicks’n’Cuts could serve as un update of this discourse. See e. g.: Rob Young: »Worship the Glitch: Digital Music, Electronic Disturbance«. In: The Wire/Rob Young (ed.s): Undercurrents. The Hidden Wiring of Modern Music. Continuum, London, ²2003: 45-58.

[xi] Allucquère Rosanne Stone: The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age. MIT Press, Messachusetts/London, 1995: 36.

[xii] David Toop: Haunted Weather. Music, Silence and Memory. Serpent’s Tail, London, 2004: 258.

Thank you to Alexei Monroe for translation support.