What you see is 75 minutes of an unchanging monochrome blue screen. What you hear is a leisurely paced interior monologue, spoken by 3 or 4 actors (John Quentin, Nigel Terry, Tilda Swinton, Jarman himself). The filmmaker starts by telling you that he is dying and is going blind … he describes his hospital treatment; there are anecdotes of daily life, jokes, reveries, memories of friends … this is collaged together with snatches of music from various members of the alternative music scene contemporary to the film itself (Vini Reilly, John Balance from Current 93, Brian Eno, Coil, Kate St John from Miranda Sex Garden), etc. The effect of this is to put you directly into the filmmaker’s head; you are listening to him think. When the film is over, you feel somehow like you have MET Jarman, or at least that you have an idea of what kind of a person he was … »I caught myself looking at shoes in a shop window. I thought of going in and buying a pair, but stopped myself. The shoes I am wearing at the moment should be sufficient to walk me out of life.«

Popularly supposed to have been conceived by its maker when he was going blind, as a result of AIDS-related illnesses – memorably listed during a two-minute passage in the film – in fact, it was conceived 5 years previous to that as – wait for it – not the last testament of a dying man, but as a great idea one night you have when you’re coming back from the pub … »We were at the Edinburgh Festival and Derek was walking down the hill and he said I have this great idea, I had this fantastic idea last night, we’re going to do this 35 mm Dolby stereo film, completely blue, Yves Klein blue with no pictures« (Simon Fisher Turner, the film’s musical director and co-composer of the soundtrack). Turner goes on to explain that the film developed over 4 or 5 years of concert performances. At the same time he was making this film, he also wrote a book, »Chroma« (1994), in which each chapter is devoted to a different colour (»white lies«, »black arts«, etc). Intended as »an antidote to the dry, academic texts on colour forced upon art students«, this book has a similar tone to »Blue« the film. Moving freely between anecdotes, historical facts and lyrical or associative chains of images –sunflowers, bananas, mustard gas, lemons, for example – it’s an artist trying to immerse us in the sensual world of colour as he experiences it for himself. He once said, »film critics have no visual training. They are writers who make pronouncements through a fog of English lit.«

Alongside Hollywood, and the narrative film industry, there is a tradition of independent film, personal filmmaking, offbeat, idiosyncratic, stylised; film as poem, rather than film as prose. This is one such film: Don’t come there looking for a story, because there isn’t one. And, here, just in case you missed that point, there aren’t any images either. It’s a personal film, you are listening to someone talking, at their own pace, not rushing, telling you something, SHOWING you something … the language is refined and worked, its not »chat« … David Lancaster of the University of Leeds describes Jarman as »hunting for a poetic rather than an intellectual truth« … The austerity of the blue screen is counterbalanced by an excess of verbal images. You see the film in your head. And that’s what makes it work. The very fact that there is nothing to look at on-screen apart from a blue screen, you are in a dark room, a cinema, with a few other people, the blue light is soft and low, after a while you stop looking at the screen (nobody stares at the light for very long). There’s nothing to DO … you cant go off and make coffee or type an e-mail, you have to give it your TIME … (he mentions at one point »the tyranny of time«), and listen to what the guy has to say, as you would if you went to visit someone at their house or in a bar … or on their deathbed. The sound collage behind the words serves to underline the mood, set the pace, and separate blocks of speech with music or atmospheres appropriate to the themes of the various sequences. I repeat: you see the film in your head. He tells you what to see, hijacking his blindness to serve as the analogy by which his personal vision is communicated directly to the inside of your skull. He wants you to know what it’s like to be him, in his situation, and to see things from his point of view.

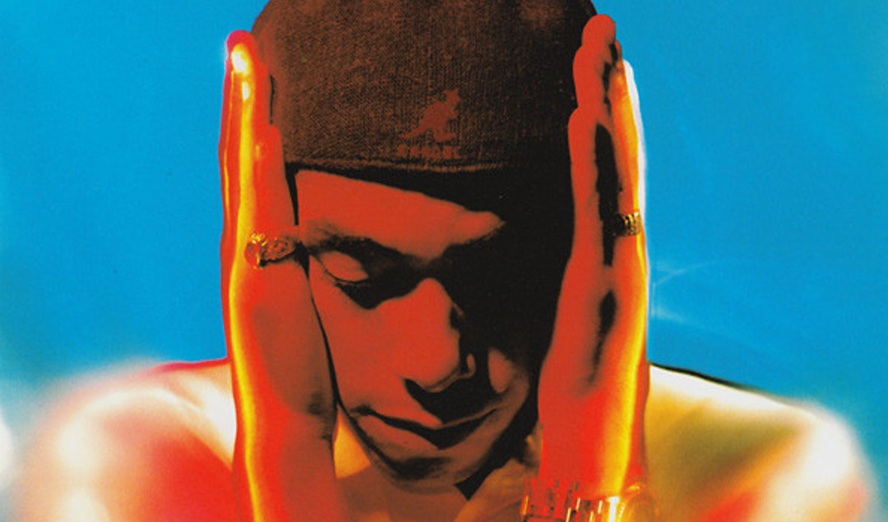

This film isn’t anti-establishment, it’s outside the establishment – consciously »our world, not their world« – Jarman was a fierce defender of what we have come to call »alternative culture«; he was gay; he made personal films, for 30 years in London (and later Dungeness); he lived & worked within a community of artists and musicians and actors; he was vocal in his opposition to Margaret Thatcher’s government, seeing them as thought police who try and tell us what to do or think. He became, in the 1980’s, something of a symbol for the independent artist who lives and works on their own terms. The right-wing British newspaper »The Daily Mail« published an obituary, 23 Feb 1994, four days after his death, written by one Christopher Tookey, entitled »How can they turn this man into a saint?«. A sniping and petty article, it upbraided him for corrupting the nation’s youth by being unashamedly gay, (of course the article said »homosexual«) and dismissed his films as being »silly«. It was illustrated with a picture of Jarman, smiling, with his arm round a man half his age, at some party.

Here’s Jarman talking, from »Blue«: A man sits in his wheelchair, he’s awry, munching through a packet of dry biscuits, slow and deliberate as a praying mantis. He speaks enthusiastically but sometimes incoherently of the hospice. He says, »You can’t be too careful who you mix with there, there’s no way of telling the visitors, patients or staff apart. The staff have nothing to identify them except they are all in leather. The place is like an S&M club.« This hospice has been built by charity, the names of the donors displayed for all to see. Charity has allowed the uncaring to appear to care and is terrible for those dependent on it. It has become big business as the government shirks its responsibilities in these uncaring times. We go along with this, so the rich and powerful who fucked us over once fuck us over again and get it both ways. We have always been mistreated, so if anyone gives us the slightest sympathy we overreact with our thanks.

I can’t see that this scene would have been any more immediate or visual, had it been filmed in a traditional way, had you seen the guy in the wheelchair, and heard and seen him speak the lines. Originally »Blue« was going to be called »Bliss«, and conceived as a »political fairy tale« … the end result isn’t so far from this original intention. The fixed blue screen is a gesture, a curtain call, a sober »fuck you« to anyone not interested in him or his ideas or listening to what he had to say.

Here’s Jarman talking again, again from »Blue«: As a teenager I used to work for the Royal National Institute for the Blind on their Christmas appeal for radios, with dear miss Punch, seventy years old, who used to arrive each morning on her Harley Davidson. She kept us on our toes. Her job as a gardener gave her time to spare in January. Miss Punch Leather Woman was the first out dyke I ever met. Closeted and frightened by my sexuality she was my hope. »Climb on, let’s go for a ride.« She looked like Edith Piaf, a sparrow, and wore a cock-eyed beret at a saucy angle.

Jarman loved gardens, and spent 20 years tending his own, which was not a traditional English garden of green lawns and rose arches, but forced out of the rocky sandy area of land at the back his seamen’s cottage in Dungeness, a bleak place on an estuary beach opposite a power station, buffeted by strong winds, where

the salt in the air makes it difficult to grow anything. There is a famous English children book, »The Secret Garden«, by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1909). It is the story of a sickly boy in an aristocratic household who never leaves his bed and never opens the curtains (»Hell is a waiting room,« Derek Jarman, »Blue«). He is rescued from the grey monotony of his existence when his vibrant young cousin comes to stay … she throws open his shutters to let in the sunlight, then takes him out into the garden and shows him a hidden door in the wall of his house that opens out into a fantastical and lush overgrown garden full of colour and life. »The further one goes / The less one knows … You can know the whole world / Without stirring abroad / Without looking out of the window / One can know the way of heaven.«

Beginning with William Blake, and »see the world in a grain of sand«, there is in English art a tradition that seeks to find the sublime in the small scale or the particular. I think of the writer Christopher Smart, whose poem »Rejoice in the Lamb« famously finds the wonders of God revealed in the details of the behaviour of his cat, Geoffrey. Or the filmmakers Powell and Pressburger, who showed us the stairway to heaven beginning in the back garden (»A Matter of Life and Death«, 1946); David Jones, an artist and writer who installed his own personal allegories of revelation in the Welsh countryside; Denton Welch, whose autobiographical novels »A Voice through a Cloud« or »In Youth is Pleasure« map his passage from sickly child to art student to accident victim, all without ever leaving Surrey. (He died aged 33.) I could even, at risk of being shot, rope in Philip Larkin, a misogynist who never left Hull, and turned down the post of poet laureate, or Charles Sprawson, whose »Haunts of the Black Masseur: The Swimmer as Hero« (1993) revived the old upper-class notion of the »European tour« to seek the sublime in a history of swimming, an activity which the author uses as a pretext to map his own autobiography. In none of these authors or filmmakers or painters (most, like Jarman, were more than one) do we find the muscular or the arrogant, all of them present a body of work which celebrates Englishness, even as it chokes on it. All are conceived on a modest scale but propose a vision of the infinite or the sublime derived from the personal. All of them contrast a repressive social background with an intense personal vision. All of them are unambiguously and cheerfully sexual, in one way or another.

Turning back to »Blue«, the tone of voice Jarman uses in his film is consciously elegant, and witty; he balances transcriptions of everyday events with effusive song-like passages, often couched in a language whose tone is more religious than secular. The film starts with him repeating the day’s news headlines (the war in Bosnia) in his local café, having put his clothes on back to front … and »since there were only two of us there I took them off and put them right then and there …« and then moves on to describe a hospital visit, but before long, we are somewhere else entirely:

»Blue of my heart

Blue of my dreams

Slow blue love

Of delphinium days

Blue is the universal love in which man bathes – it is the terrestrial paradise.«

The whole film is structured like this: sequences that move backwards and forwards between often painful personal experience – the narrative is, after all, a first-hand description of what it’s like dying, and seeing your friends dying – and more effusive, ornate, or elegiac, sequences of poetry, music and song (Kate St John’s modern madrigals often repeat, sung, lines you have just heard spoken). Jarman once said, if you put 32 sequences together, then you get a feature film … that feels about right here. From Blue: »The Gautama Buddha instructs me to walk away from illness, but he wasn’t attached to a drip.« In another passage during the film he says, »once in a while I dream a dream, as magnificent as the Taj Mahal.« That he mentions this frighteningly ornate and over-decorated building – the biggest cake of them all – in the context of a film where, in terms of what we see on-screen, reductionism can go no further, is typical: we’re back in the secret garden again, but this time you get there, not through a door in the wall, but through a door in your head…

Jarman grew up in the South of England, and saw his childhood as belonging to an eternal tea-time twilight of Englishness, the original »waiting room«, if you like: fancy that, mustn’t grumble, can you pass the gravy, Church of England, do as you would be done by, I don’t mind if I do. I sit there, you sit there, do you mind if I hang myself? His retort to this was to replace inhibition with exhibition, celebrate life, and make films (with his friends) that were iconoclastic and inventive, a mix of the gleefully trashy and the self-consciously formal, sometimes deliberately irritating, never pompous, and always as the French say »pédé comme un phoque«.

»The smell of him

Dead good looking

In beauty’s summer

His blue jeans

Around his ankles

Bliss in my ghostly eye

Kiss me

On the lips

On the eyes

Our name will be forgotten

In time

No one will remember our work

… I place a delphinium, blue, upon your grave.«

»There are no resources to brighten the place up,« Jarman says at one point of a hospital – here’s a film (with, by conventional standards, no resources) that seeks to do exactly that, to brighten the place up – the place inside our heads where we dream ourselves to ourselves.

Another independent filmmaker, the American JX Williams, once wrote this: »There comes a time in your life when you’ve got to confess to yourself: You’re never gonna make Citizen Kane. You’re never gonna get the girl. Tonight’s not your Night and if you ever had a Night, it happened a long time ago and you blew your wad. All you can really hope for is to get a big footnote in a book somewhere. The credits roll. The curtain drops. And that’s that.« Well, Jarman had it both ways: he didn’t want to make Citizen Kane – his films celebrated independent cinema as a necessary and vital alternative to mainstream narrative cinema. He avoided the epic. His answer to »never gonna get the girl« was to spend a happy life screwing men. Tonight was often his night. »Blue« isn’t a »Citizen Kane«, for sure, but it’s definitely a big footnote somewhere.